Thomas Ruys Smith explores the presence of Halloween in 19th-century America.

Halloween may have originated as an Old World tradition. Still, during my upbringing in the United Kingdom in the final decades of the twentieth century, it was primarily observed as a faint recollection of folk traditions or a somewhat subdued adoption of American festivities.

As Lucy Mangan recently expressed in The Guardian, ‘I didn’t encounter a pumpkin until I turned 21, in the garden of a posh friend from university.’ Nevertheless, this didn’t deter me from avidly observing fragments of Halloween that made their way back across the Atlantic through diverse elements of popular culture. I found solace in realizing that I was not alone in this experience, as Neil Gaiman similarly conveyed in the New York Times in 2006:

When I was growing up in England, Halloween was no time for celebration […] I did not believe in witches, not in the daylight. Not really even at midnight. But on Halloween, I believed in everything. I even believed that there was a country across the ocean where, on that night, people my age went from door to door in costumes, begging for sweets and threatening tricks.

Exploring Halloween In 19th-Century America

This year, I decided to merge my long-standing fascination with Halloween and my professional role as a lecturer in American Studies. I delved into how Halloween was observed (or at least documented) in nineteenth-century America as part of the annual Countdown to Halloween blogging marathon on American Scrapbook. During this past month, I extensively explored nineteenth-century popular literature, searching for Halloween-themed material.

I discovered that, at least concerning Halloween, the past represents a different realm where traditions diverged significantly. Throughout much of the nineteenth century, one would struggle to find ghost stories, pumpkins, or any of the imagery immediately associated with contemporary Halloween.

Surprisingly, Christmas, not Halloween, dominated the holiday season associated with spooky tales. Jeffrey Weinstock, in his work “Scare Tactics: Supernatural Fiction by American Women,” notes that Charles Dickens played a pivotal role in linking ghost stories to Christmas with the publication of “A Christmas Carol” in 1843, as well as through his advocacy for supernatural tales in Christmas annuals.

Antiquarian Traditions Of All Hallow’s Eve In The 19th Century

While Halloween in the nineteenth century may not have featured the familiar elements associated with it today, it possessed its own enduring set of associations. To comprehend the antiquarian traditions of All Hallow’s Eve during this period, we must harken back to the eighteenth century, with Robert Burns’ poetic work “Halloween” from 1785 offering a definitive insight into the meaning of the holiday on both sides of the Atlantic during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Burns establishes the supernatural essence of Halloween, describing it as a night when witches, devils, and mischievous entities roam freely on their malevolent midnight errands.

The poem, however, primarily delves into the plethora of charms and spells associated with the night, particularly those centered around love and prophecy, prevalent among the peasantry in the west of Scotland. Although these fortune-telling traditions have largely faded away in contemporary times, they were prominently featured in Halloween stories from the first half of the nineteenth century.

An exemplary illustration is Timothy Shay Arthur’s 1849 short story titled ‘Love Tests of Halloween,’ which directly references Burns’ poem. Arthur’s narrative also underscores two significant aspects of Halloween during the mid-century: its popular association with Scotland (and Ireland) and the perception that the day’s observance was gradually waning.

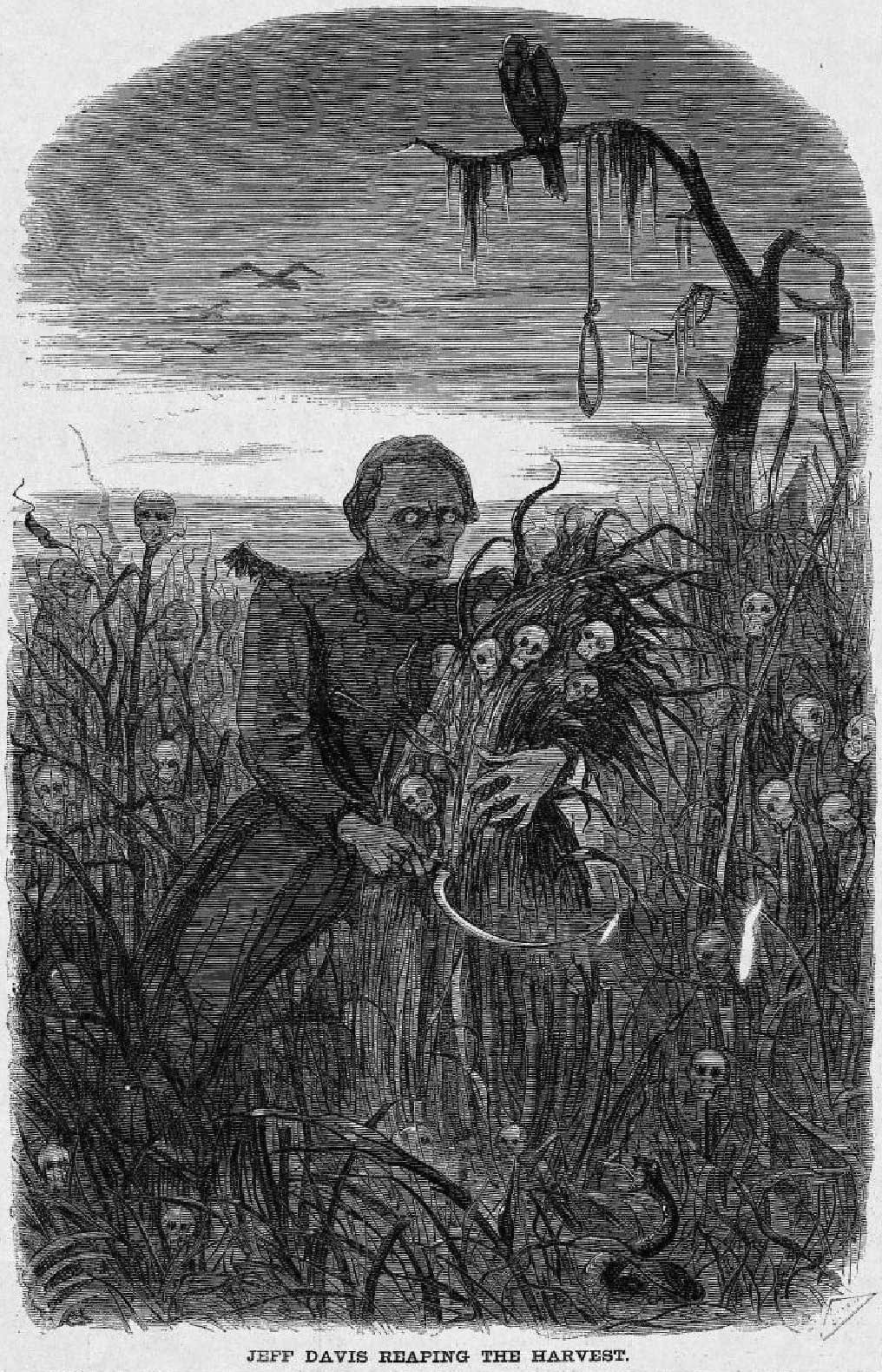

Post-Civil War Shift In Halloween Emphasis

While the association of Halloween with love spells persisted throughout the century, a notable shift in the prominence and emphasis of Halloween emerged following the American Civil War (1861-1865). Ronald Hutton, in “The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain,” attributes the revitalization of Halloween in America during this period to the significant Irish immigration that followed the Great Famine, bringing with it a deep-rooted observance of the festival.

Charles James Cannon’s 1855 novel, “Bickerton; or, The Immigrant’s Daughter,” provides literary evidence by describing Halloween festivities in Boston’s ‘Little Dublin’ neighborhood as a custom of ‘heathen times’ involving ‘superstitious practices.’ Despite being labeled as such, it was a day of ‘mirth’ eagerly anticipated by the young for months. The resurgence of Halloween aligns with the post-Civil War era’s growing fascination with and nostalgia for local customs and folk traditions, marking a profound cultural shift in American society.

Gradually, a more familiar Halloween culture begins to take shape. In 1860, a year preceding the Civil War, the widely acclaimed writer E. D. E. N. Southworth released ‘The Spectre Revels,’ a tale of a haunted house unfolding on Halloween. Subsequently, in 1865, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle featured a Halloween-themed parody of the poem ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas’—commonly recognized as ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas’—published in its October 31st edition.

‘Twas the night of All Hallows, when goblin and sprite,

Were to roam, it is said, on that terrible night.

Halloween In Literary Journals And Educational Recommendations

In the concluding decades of the 19th century, major literary journals consistently featured Halloween-themed stories in their October editions. Examples include William Black’s ‘A Halloween Wraith’ in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1890 and Hezekiah Butterworth’s ‘A Halloween Reformation’ in the Century Magazine in 1894.

By 1905, educational perspectives were also shifting, with Kindergarten Magazine advising teachers to dedicate a few days in October to the spirit of Halloween, allowing fun and frolic to prevail during this period.

The same pattern can be verified using Google Book’s new Ngram viewer, enabling users to explore the prevalence of a word or phrase across their extensive scanned archives.

A noticeable but relatively modest increase in the word usage became apparent around 1860. However, when compared to the remarkable surge in Halloween’s popularity after the turn of the century, the earlier uptick appears insignificant.

Regardless of the perspective, it is evident that the contemporary concept of Halloween is predominantly a creation of the twentieth century. However, we can trace the foundations of this influential cultural tradition back to the ephemeral remnants of Halloweens gone by. Perhaps, there’s a possibility that love spells might experience a resurgence?

Also Read: Felix Guattari’s Desiring Machine