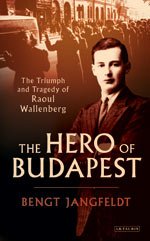

The tale of Raoul Wallenberg, who, at great personal peril, saved numerous Jews in Budapest from the horrors of the Holocaust, stands out as one of the most extraordinary narratives of World War II. However, the full story of his life and ultimate fate can be comprehensively narrated. In an excerpt from “The Hero of Budapest,” the inaugural work to piece together the events surrounding Wallenberg’s capture and vanishing, Bengt Jangfeldt offers insight into creating the ‘protective passports’ propelling Wallenberg into prominence.

The Birth Of Raoul Wallenberg: A Positive Omen

When Raoul Wallenberg entered the world, his grandmother remarked, “Little Raoul was born ‘with the caul,’ as they say. For those who are superstitious, this is supposed to hold positive significance – although what that might be, I do not know. I was pleased that he was a Sunday’s child. May it be a good omen.”

Indeed, it proved to be one. In the final stages of World War II, Raoul Wallenberg orchestrated one of the most remarkable humanitarian rescue missions ever undertaken by an individual.

Within just under eight weeks following Germany’s takeover of Hungary in March 1944, nearly half a million Hungarian Jews met their demise. This marked the largest deportation effort of the entire war, described by Winston Churchill as “probably the greatest and most horrible crime ever committed in the history of the world.”

In July, Wallenberg embarked on a diplomatic mission led by the Americans to Budapest, entrusted with the imperative task of averting the gassing of the quarter-million Jews who remained alive.

Also Read: A City of the Dream

Wallenberg’s Humanitarian Endeavors In Budapest

The rescue initiative initiated by Wallenberg in Budapest was of remarkable magnitude. He introduced a novel document known as the ‘protective passport,’ which granted nearly 10,000 Jews Swedish citizenship, thereby sparing them from deportation and certain death. Although he primarily earned renown for his Schutzpass, an equally significant aspect of his mission was establishing an extensive social support system.

Wallenberg organized healthcare services, distributed food supplies, and established shelters for children and the elderly. Through these humanitarian efforts, thousands more individuals were rescued from the brink of starvation and demise.

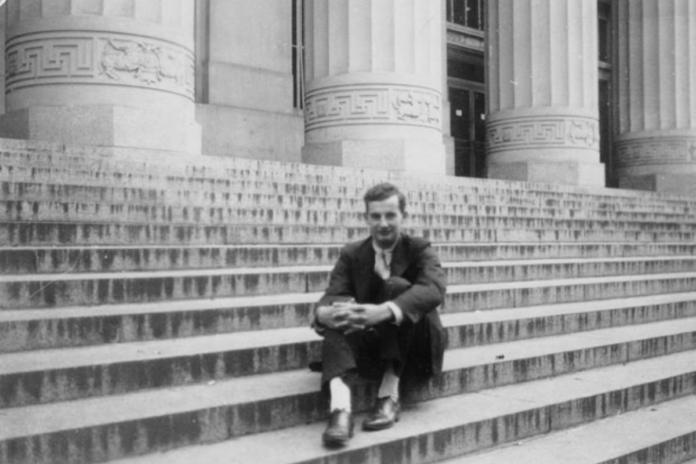

Raoul Wallenberg’s Early Life And Privileged Upbringing

Born in 1912, Raoul Wallenberg hailed from a prominent business family rather than a diplomatic background. Socially, he was considered fortunate, having been born into Sweden’s foremost dynasty of financiers, which promised him a seemingly carefree future.

Raised in Stockholm’s most affluent neighborhood, he attended prestigious schools and mingled in elite social circles. However, a profound sadness marked his upbringing, as he was fatherless from birth and primarily raised by his paternal grandfather, Gustaf Wallenberg, who was the brother of Marcus Wallenberg, the head of the Wallenberg family.

Raoul’s grandfather played an indispensable role in his upbringing, as he established the framework for Raoul’s education funded his studies, and outlined the moral principles he wished Raoul to abide by. He envisioned his grandson as a diligent businessman, a global citizen, and someone who would bring pride to the family name.

Upon Raoul’s 23rd birthday in 1935, Gustaf Wallenberg penned a letter expressing his aspirations for Raoul, hoping that he would fulfill the family’s expectations and bring honor to their name. Being a part of the Wallenberg family carried significant responsibilities.

Raoul Wallenberg’s Unconventional Career Path

Raoul, displaying a keen interest in aesthetics from a young age, initially pursued architecture at the University of Ann Arbor in Michigan. He then worked as a businessman and banker in Cape Town and Haifa. Upon returning to Sweden in 1936 after five years abroad, he intended to embark on a career in business.

However, despite his determination and recognized negotiation skills, he did not achieve notable success as a businessman. However, his mission in Hungary showcased the invaluable nature of these attributes, possibly marking it as unparalleled in diplomatic history: a Swedish diplomat – not formally recognized as such but rather a businessman – was dispatched to Hungary on a mission initiated and outlined by a foreign state, the USA.

Raoul Wallenberg’s Remarkable Mission and Tragic Fate

The mission placed significant demands on Wallenberg’s ability to take initiative, unconventional thinking, and organizational skills. The auspicious caul he was born with proved to be beneficial indeed – for the Jews of Budapest, though not for himself. In January 1945, the Soviet army apprehended him and transported him to Moscow, where he was subsequently imprisoned and, in all likelihood, executed two and a half years later.

Thus, the narrative of Raoul Wallenberg encompasses not only his remarkable achievements on behalf of Budapest’s Jews but also the heavy price he paid and his fate in the Soviet Union, which, even 68 years after his abduction, remains shrouded in mystery.

In the autumn of 1944, Budapest became a battleground where the front line was drawn between the two dominant totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century. Raoul Wallenberg found himself ensnared in this conflict, emerging victorious against one ideology but ultimately falling prey to the other.

Bengt Jangfeldt, author of the recently published biography “The Hero of Budapest: The Triumph and Tragedy of Raoul Wallenberg,” offers the first comprehensive account of Wallenberg’s fate. His biography “Axel Munthe: Bengt Jangfeldt earned the Swedish Academy’s biography prize for “The Road to San Michele,” initially released in Swedish in 2003 and later translated. Additionally, his extensive biography “A Life at Stake,” centered on the renowned Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, was published in 2007 and awarded the August Prize for best non-fiction book of the year, Sweden’s equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize.

Also Read: Post Marcs