“Aristocrats and Archaeologists” tells the story of an Edwardian journey on the Nile in the winter of 1907–1908. At its core is a remarkable series of letters that provide a first-hand account of the three-month trip—the sites visited, the passengers aboard and the people encountered ashore, the clashes of culture and of class. More than a mere travelogue, this correspondence from over a century ago opens a window into the rarefied worlds of aristocracy and archaeology during their golden age. What emerges is a vivid picture of privilege and adventure that continues to enthrall.

Read an exclusive extract below…

Ferdy’s letters

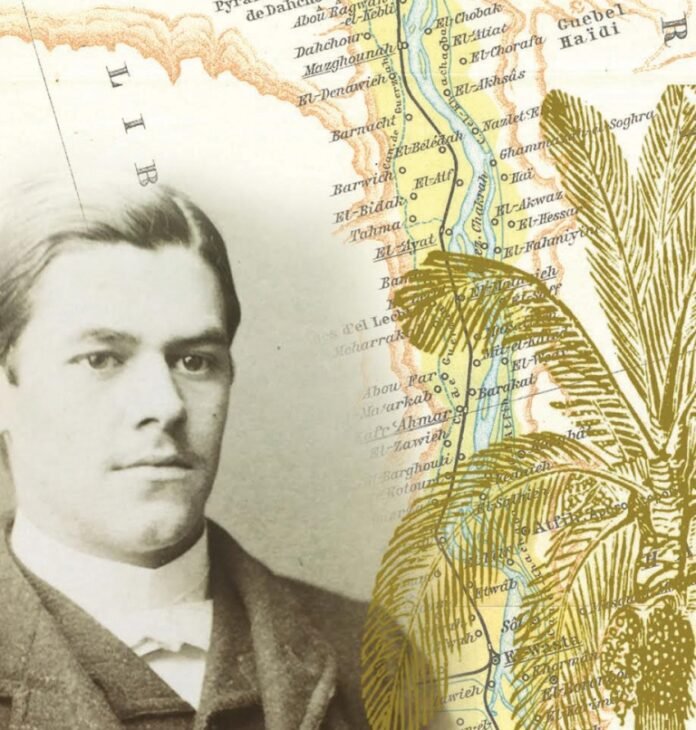

In 2006, I met Julian Platt at a college reunion. On learning that I was an Egyptologist, Julian mentioned a collection of letters he had inherited from his cousin and godmother Violet. They had been written by Violet’s father, Ferdy, during a trip up the Nile in the early twentieth century. Would I be interested in reading them? They sounded intriguing. Yes, I replied.

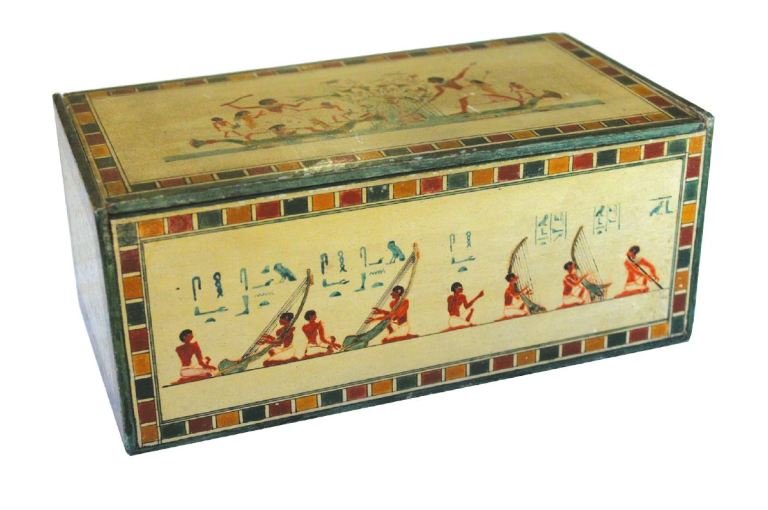

The loose bundle of letters arrived in a padded envelope, together with photographs of the small, painted box in which they had been stored for decades. Undoubtedly, the maker of the box had been an accomplished artist: the scenes on the long sides were faithful reproductions of ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. But what really caught my eye were the hieroglyphic inscriptions painted on the two short sides of the box: no mere jumble of random signs, they looked like well-crafted sentences. Indeed, one inscription read,

Year 13 month 8 day 30 under the Majesty of George, fifth of that name. Says the physician Ferdinand, “Behold, I have painted this box with my own hand for my daughter whom I love, Violet. I did this in order that my memory may remain firm in the heart of my daughter and that my name may be in her mouth.”

While the second inscription stated,

Behold, this box belongs to the maiden Violet. Her mother was the mistress of the house, Mabel; her father was the physician, Ferdinand. He says, “I have spoken with words of magical power over this box. If anyone injures it or damages the writing upon it, my curse shall reach them wherever they may be.”

This was my first introduction to A.F.R. Platt, the writer of the letters that had been kept, forgotten and unread, in his hand-made box for so long. All I knew from Julian was that “great uncle Ferdy” had made the box for his daughter as a memento on his return from Egypt. His account of the trip, undertaken as private physician to the Duke of Devonshire, was contained in the letters he had written home to his wife Mabel (May) every few days during his long sojourn in the Nile Valley.

It was immediately clear that Egypt must have made more than a passing impression on Ferdy: the painted box showed a keen appreciation of ancient Egyptian art, while the inscriptions, accurately rendered in grammatically correct ancient Egyptian, indicated a near-professional knowledge of hieroglyphic writing. “The physician Ferdinand” had clearly been an amateur Egyptologist of some distinction. Still, my first reaction was that his letters home would perhaps be unlikely to hold much interest a century later.

Yet, as I opened the bundle of correspondence and started to read, Ferdy’s words leaped off the page and began to fire my imagination. His letters—carefully inscribed on sheets from a “Medieval Cream wove bank writing tablet” until it ran out in furthest Nubia—brought vividly to life a lost world: of Edwardian travel, of Egypt on the brink of the modern age, of the great figures of Egyptology, of aristocrats and archaeologists. Ferdy’s letters were nothing less than a time capsule, a rich evocation of a vanished era, a first-hand account of the Edwardians’ encounter with Egypt. As I read on, it was clear that Ferdy’s letters also revealed his private thoughts, the intimate feelings of the man behind the professional exterior. Here, in short, was a correspondence of rare scope and richness. It clearly deserved a wider readership.

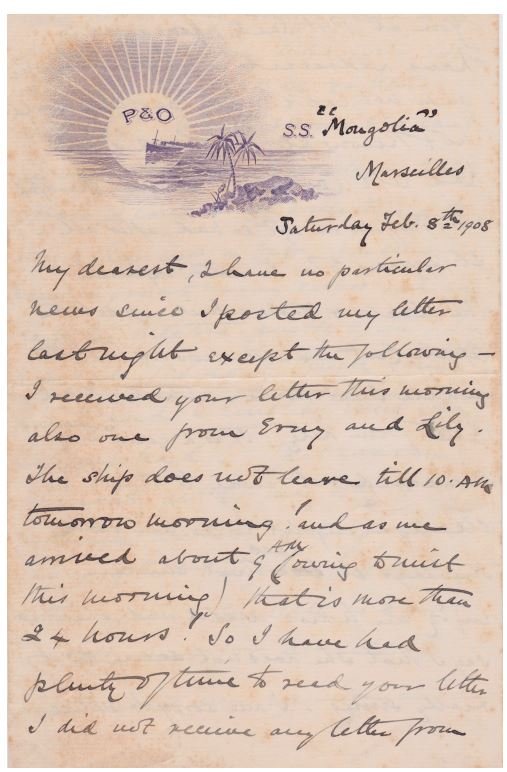

Pages 106-110 – one of the letters

SS Serapis, Luxor

Wednesday, Jan. 22nd 1908

My dearest, I was glad to hear all the news in your letter received yesterday, but you didn’t say how your cold is, so I suppose you are well again. You have had the most extraordinary weather in England. For two reasons, I find it difficult to form a connected idea of what goes on in England: it takes a week for a letter to arrive, but the Duke gets a bundle of press telegrams.

I hear little scraps before I see the weekly Times and . . . the weather I get hopelessly mixed up with telegrams, your letters and newspapers. I was anxious [to] know how Violet enjoyed the Wilmers’ party. She must have looked a dear little soul in the dress you made her. I was sorry she missed the Davis party.

I shall be glad to [see] you and the children again. I almost regret having arranged to come home by the long sea; still, I think it best for me as I should feel the cold so much and I do hate railway traveling, especially at night. I am sorry I can’t go down to Cairo by boat as I must travel at night. Leaving Luxor at 6.30 and arriving at 8am the next morning.

I shall stay a night or two in Cairo as I do want to see the Museum. It was a great disappointment that I could not do so before we left Mena House. The Duke was so bad that I disliked being out of the way.

Did I tell you that I was hailed by Whymper, the artist, just as I went on board the other day? He is sharing a database belonging to another artist named Nicol.

On Sunday I went there to have a chat as W[hymper] hadn’t talked to anyone for a fortnight, so we were both glad of the chance. I met Howard Carter there. I met him at Deir El Bahri when I was in Egypt before; he [was] an artist and quite a young fellow in those days.

He was copying the paintings in the temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir El Bahri. Sometime after that, he was made Inspector of Antiquities. Two years ago, he had a row with some French tourists, and although he was exonerated, he was asked to write a letter saying he was sorry it had happened, but he declined and had to resign.

He has now gone back to painting. He asked me over to lunch with him on Monday. I went over early and climbed to the top of the mountain at the back and to the left of Deir El Bahri. It is much higher than the cliff [over]looking Deir El Bahri, and although a very stiff climb, it well repaid the trouble, as the view from the top was magnificent.

It took more than an hour to get to the top (not counting rowing across), and the donkey rides to Carter’s house, which really belongs to the Government. It was erected for the use of the Service of Antiquities, but as it was not wanted this year, Maspero gave him permission to live in it.

I had lunch with him and Nicol the artist who is staying there for a time with Carter while Whymper is on his boat. Carter has done some very beautiful work. He copies some of the best Egyptian figures or scenes very accurately as to the matter of outline and general color.

He leaves out all the cracks and damage and restores what is left. But the great charm is that he shades the colors to make it look real; for instance, the golden vulture headdress of a queen he has shaded in such a way that without altering the drawing in the least, it looks like real gold. I will tell you more about it when I get home.

After lunch I went with Carter to the Tombs of the Queens and saw the tomb of Queen Nefert-Ari, the wife of Rameses II. She is the queen I have just mentioned and it was in this tomb he copied her painting.

She was a beautiful woman and Carter’s painting brings this out wonderfully. I have never seen pictures of anything Egyptian that I have longed to buy and possess. If I had the money spare, I would buy this particular picture without a moment’s hesitation. As you can imagine, Carter’s loss of his appointment is a serious thing for him, and he was and is, I believe, very hard up.

I told the Duke about him and he has asked me to go over to Medinet Habu with him to see Carter’s sketches as he wants to help him by buying some. I am very glad to have been the means of doing this. I wish I could buy some myself.

He has done a sweet little piece of one of those fowling scenes like the one in my consulting room. It represents the little daughter who is not sitting between her father’s feet as in mine but standing on the back of the green punt and holding against her breast a little nestling bird.

It is beautiful. The tombs that I saw in the Valley of the Tombs of the Queens are quite new to me as they have been open since I was in Egypt last. Some of them are in an excellent state of preservation, and the colors are quite fresh.

Some of the blues are very vivid. Nefert-Ari’s tomb is very big, and the work fine, considering that it is from the XIX Dynasty. I enjoyed the day very much and did not get home till long after sunset. I was at Karnak yesterday afternoon.

The Dr. on the Rameses, who is here now, called on me and asked me to dine with him on board tonight. His name is Jackman, and he lives in Brighton. I met him at Assuan when I went on board to see if they had a book on board I wanted.

I don’t think I have any more news for you at present. It has been very chilly at night since we came here, and even during the day, it has never been very hot. I hope by now you have received my latest batch of letters from Assuan.

Yours received yesterday, dated 13th–14th Jan., only speaks of receiving my 1st letter from Wadi Halfa on the way up. But I expect I shall hear from you on Friday or Saturday. I look forward to your letters very much although I don’t say much about them in mine. As I have mentioned before, you naturally prefer to have my news and not comments on yours. I was glad to know that Violet enjoyed getting my letter.

We had a man and his wife named Alexander to lunch yesterday. I don’t know who they are, but they came out in one of those new steamers, and she has lost her trunks and all her dresses, and they say they never put them ashore.

I dare say you saw there was a strike of stokers who got at the champagne, and all got drunk, and one stole some clothes out of a passenger’s cabin. The waiters, too, being hotel waiters, were all seasick! So there was no one to wait.

Much love to you, darling, and the chicks. Also, to No. 10, remember me to the Hamptons and “absent friends”.

Your loving husband

Ferdy A.F.R. Platt

~