Brand New Art From China is the title of a book by Barbara Pollack, a renowned critic and curator of contemporary Chinese art.

Xu Zhen holds a significant role in the Chinese art scene, bridging the gap between the older generation of artists who emerged in the early 1990s and the younger generation, many of whom were born after 1980. Despite being born in 1977, Xu Zhen is relatively young himself.

However, his extensive exhibition history and impactful work have already established him as a leader and mentor for emerging artists. He began his career in Shanghai without attending art school, initially gaining attention through a series of provocative videos. Today, he earns renown for his versatility, as he has explored various mediums including painting, photography, video, sculpture, and installation.

Read: One Stand There As Though Mesmerised: An Extract From DESERT LOCUST PLAGUES By Colin Everard

Artistic Transformation: Xu Zhen’s Transition To CEO Of MadeIn

In 2009, at 32, Xu Zhen made a bold move by renouncing his identity as a solo artist and instead assuming the CEO role for an art-making company humorously named MadeIn, a nod to the ubiquitous labeling “Made in China.”

Having accumulated a decade of art exhibitions, Xu Zhen was aware of the challenges Chinese artists face in evading categorization by foreign curators and the expectation that their work should reflect Chinese culture.

From the outset of his career, he appeared determined to defy such categorizations, and with MadeIn, he found a platform to challenge and subvert stereotypes.

Subversive Artistry: MadeIn’s Satirical Sculptural Exhibitions

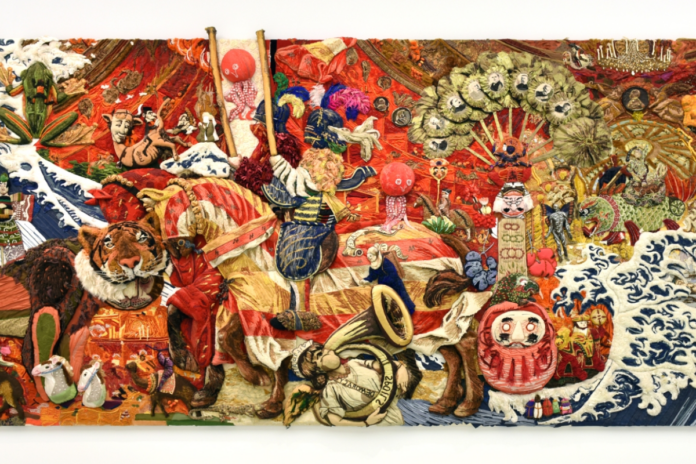

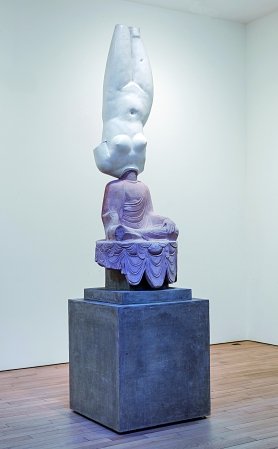

MadeIn’s most recent exhibitions showcased at the Ullens Center in Beijing in 2014 and the Long Museum a year later, offered visitors a striking display of mammoth sculptures. These sculptures ingeniously amalgamated elements from Greek and Chinese antiquities, contorting and combining them in a manner that humorously undermined the traditional notion of East-West encounters.

Brand New Art From China covers topics such as the impact of the Internet and social media on Chinese art, the role of women and LGBTQ artists in challenging the norms, and the influence of Western art and theory on Chinese art.

For instance, visitors encountered replicas of Greek and Buddhist statues merged unexpectedly, such as a replica of Winged Victory positioned upside down atop a headless bodhisattva, or a line of Greek warriors reimagined as a multi-armed deity.

Rather than merely offering inspired revisions of classical icons, MadeIn’s works played on viewers’ expectations. They critiqued the practice of merging cultural artifacts, often with a satirical edge that may have been lost on some viewers encountering the pieces for the first time.

“I have a nuanced connection with Chinese traditional culture,” Xu Zhen shared with me during an interview prior to the opening of the MadeIn retrospective at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing. “It’s akin to the relationship with your parents—there’s love, yet inevitably, conflicts arise in real life. I believe these statues have the capacity to embody various intricate emotional dimensions.”

Artistic Subversion: MadeIn’s Exploration Of Cultural Identity

Xu Zhen and MadeIn have frequently opted to forgo direct references to Chinese culture, instead seamlessly blending symbols to provoke total bewilderment. During one of MadeIn’s early exhibitions, the company presented a comprehensive survey of “art from the Middle East,” melding aesthetic strategies from conceptual art practices with enough stereotypes of the war-torn, Islamic-dominated region to evoke a Middle Eastern identity.

The exhibition featured mosques constructed from Styrofoam, tapestries incorporating Charlie Hebdo political cartoons, sculptures crafted from barbed wire, and a field of broken bricks set upon an invisible waterbed, creating the illusion of a silent earthquake.

When the James Cohan Gallery in New York displayed these works in 2009 under the title “Lonely Miracle: Art from the Middle East,” most visitors assumed they were the creations of a collective of Arab artists—an intentional misdirection.

MadeIn’s approach underscores how easily cultural identity can be manipulated in today’s globally driven art world, as it employs irony and cultural references to imbue works with a sense of locality.

Challenging Artistic Identity: Xu Zhen’s Provocative Approach

Xu Zhen once remarked to me, “Anyone can be a Chinese artist,” citing the example of an American artist assuming the identity of Zhang Xiaogang, a renowned Chinese artist known for his poignant portrayals of one-child families and Cultural Revolution themes.

Aware that Western viewers often sought cultural artifacts and evidence of global sophistication in their art acquisitions, Xu Zhen opted to subvert these expectations rather than cater to the market. By allowing MadeIn to produce his artworks, Xu Zhen demonstrates that if anyone can embody the essence of Chinese art, then anyone can be Xu Zhen.

Brand New Art From China explores the new generation of young Chinese artists who are emerging in the global art scene, and how they negotiate their cultural identity and heritage in their work.

Barbara Pollack is a highly acclaimed journalist, art critic, and curator renowned for her expertise in contemporary Chinese art. Prestigious publications like Vanity Fair, The New York Times, and the Washington Post have featured her articles and numerous other prominent outlets such as the Village Voice, Artnews, and Art in America. Pollack has authored groundbreaking monographs on emerging Chinese artists and notably penned the first published artist profile of Ai Weiwei for Artnews in 2005. She frequently delivers lectures across the United States and Asia and was the keynote speaker at the 2018 Art Basel Hong Kong event.

Also Read: Don’t Fear Newspapers, Fear the People By Tia O’Brien