The following article for Shoah is from Nathan Abrams’ recent publication, “The New Jew in Film.”

In Judaism, people place significant importance on matters related to bodily functions, such as going to the toilet, and the concepts of ritual purity and defilement that arise from them.

This emphasis is evident in both the Torah and subsequent Talmudic literature. People accompany the act of relieving themselves with their own dedicated blessing in Judaism.

The Bible underscores personal cleanliness’s significance for physical well-being and spiritual purity. Accordingly, people positioned latrines outside the boundaries of military camps in ancient times to maintain cleanliness.

Each soldier was provided with a tool, such as a spade or trowel, to dig a hole and bury their waste, as outlined in Deuteronomy 23:13–15.

Also Read: John Bright And America

In later Jewish tradition, the rabbis expanded on the importance of cleanliness by requiring handwashing after urination and defecation.

They also engaged in extensive discussions regarding whether it was permissible for a Jew to pray in or near a toilet and under what circumstances, especially concerning the presence of urine and excrement.

The concern drove efforts to delineate clear boundaries between sacred and profane spaces, particularly concerning toilet facilities, as the sanctity of prayer could be compromised by the proximity to a place associated with bodily waste.

Even in contemporary Haredi culture, people give significant attention to bodily functions and their management. They treat rituals such as urination with meticulous care, often involving precise protocols and supervision.

This emphasis reflects a broader cultural preoccupation with bodily purity and its intersection with religious practices.

The Symbolism Of Bathrooms In Holocaust Films

In films addressing the Holocaust, bathrooms often symbolize the stark division between life and death. Throughout the camps, washing facilities served as ominous reminders of mortality, with gas chambers disguised as shower rooms.

Movies like “The Grey Zone” and “The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas” vividly depict the chilling deception. In “Schindler’s List,” a haunting scene unfolds as guards coerce a group of women prisoners into a chamber labeled “Bath and Inhalation Room.”

Their fear and desperation are palpable as they await their fate, uncertain whether the showerheads will release water or deadly gas. This pivotal moment captures the agonizing tension between hope and despair as the women anxiously anticipate their destiny.

Like Alfred Hitchcock, Spielberg employs the shower motif to evoke a sense of fear and apprehension in his film. In another scene from the movie, a young Jewish inmate, a New Jew in a concentration camp, inadvertently fails to clean a bathtub properly, leading to a tense encounter with Amon Goeth in his bathroom.

Initially pardoning the boy, Goeth later reverses his decision and tragically shoots him dead. In a poignant moment, children resort to hiding in feces to evade being selected for the gas chambers.

A very young boy desperately seeks refuge, illustrating the harrowing lengths individuals went to in order to escape the horrors of the Holocaust.

The Unlikely Refuge: Latrines in the Camp

Discovering that the spots he intended to hide in are occupied, the young boy resorts to dropping down through the hole of the wooden latrines into the sewage below. Covered in feces, he finds himself surrounded by four other children who assert their claim to the space, telling him to leave.

Despite the repulsive conditions, the latrines in the camp serve as an unexpected sanctuary and place of safety for these vulnerable individuals. At the start of the film, Jews resort to using the sewers to evade being forcibly removed from the ghetto, unfolding a parallel scene.

While the sewers offer a means of escape for some, they also harbor danger, as evidenced by the discovery and subsequent shooting of other escapees. Thus, the sewers serve as both a route to potential freedom and a pathway fraught with peril and potential tragedy.

The Dehumanizing Role Of Toilets In The Holocaust

The use of toilets during the Holocaust served as a powerful tool for the humiliation and degradation of Jewish individuals. Given the vast number of Jews targeted by the Nazis, toilets likely became perceived as inherently Jewish, as they were highly public spaces.

The absence of toilets in the cattle cars transporting Jews to death camps meant that acts of defecation and urination occurred in full view, serving as deliberate tactics by the Nazis to systematically dehumanize their victims before their eventual extermination.

This deliberate degradation, witnessed by both perpetrators and victims, played a crucial role in distancing the Jews from their humanity, reinforcing the perpetrators’ belief that they were not extinguishing human lives but rather disposing of mere “pieces.”

Films like “The Grey Zone” and “The Counterfeiters” portray toilets as spaces of profound humiliation for Jewish prisoners.

In “The Grey Zone,” viewers witness an elderly Jewish woman using a bucket in the crowded confines of a train, highlighting the victims’ experience of transportation to concentration camps with a stark portrayal of the lack of privacy and dignity.

Similarly, in “The Counterfeiters,” an SS guard humiliates Jewish prisoner Salomon Sorowitsch by urinating on him as he cleans the toilet. This degrading act, occurring within the confines of the bathroom, highlights the stark power imbalance between captors and captives.

In the bathroom, dominance is asserted through physical and verbal confrontations, turning it into a battleground.

Symbolism Of Toilets In “La Haine”

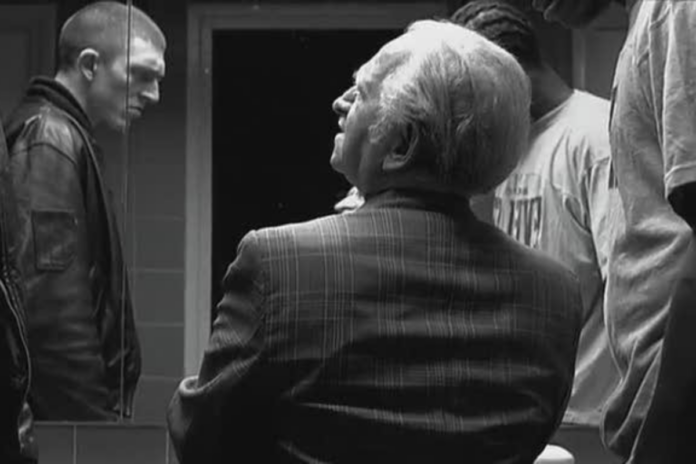

In a notable and thought-provoking scene from “La Haine,” New Jew director Kassovitz deliberately chooses a public toilet as the setting to introduce a Holocaust survivor character, Tadek Lokcinski.

This choice underscores the thematic link between victimization, humiliation, toilets, and the Holocaust, encapsulating the stark juxtaposition of “God, shit, and deportation” as described by Rose.

The fact that the scene takes place in the bathroom of a Parisian café adds another layer of significance. Lokcinski, portrayed as Eastern European, particularly Polish, through his physical appearance and Yiddish-accented French, shares a poignant story with three bewildered youths.

He recounts the tragic tale of his shy friend Grunwalski, who, while relieving himself in the woods, missed his train to a Siberian gulag. As the train departed, Grunwalski failed to rejoin it after his trousers fell down, leading to his death from exposure.

Despite the destination being a Russian labor camp, catching the train could have potentially saved Grunwalski’s life, as many Polish Jews who survived the Holocaust escaped to the Soviet Union following the German invasion of Poland.

Interpreting The Ambiguity In “La Haine”

Similar to the Coen brothers’ “Goy’s teeth” scene in “A Serious Man,” the moral ambiguity in “La Haine” leaves the audience questioning the old man’s intentions. Is he admonishing the youths to prioritize correctly, unlike his unfortunate friend Grunwalski?

Or is he cleverly using his Yiddish wisdom to extricate himself from a potentially threatening situation by confusing the three youths, who clearly fail to grasp the essence of his story?

Loshitzky’s observation underscores the thought-provoking nature of this narrative detour, which confronts viewers with the vulnerability and helplessness associated with Jewish experiences during the Holocaust.

The metaphorical significance of being “caught with their pants down” in the scene adds layers of complexity, inviting viewers to contemplate the deeper implications of the old man’s tale within the context of Jewish history and identity.

Also Read: Palestine In Israeli Schoolbooks