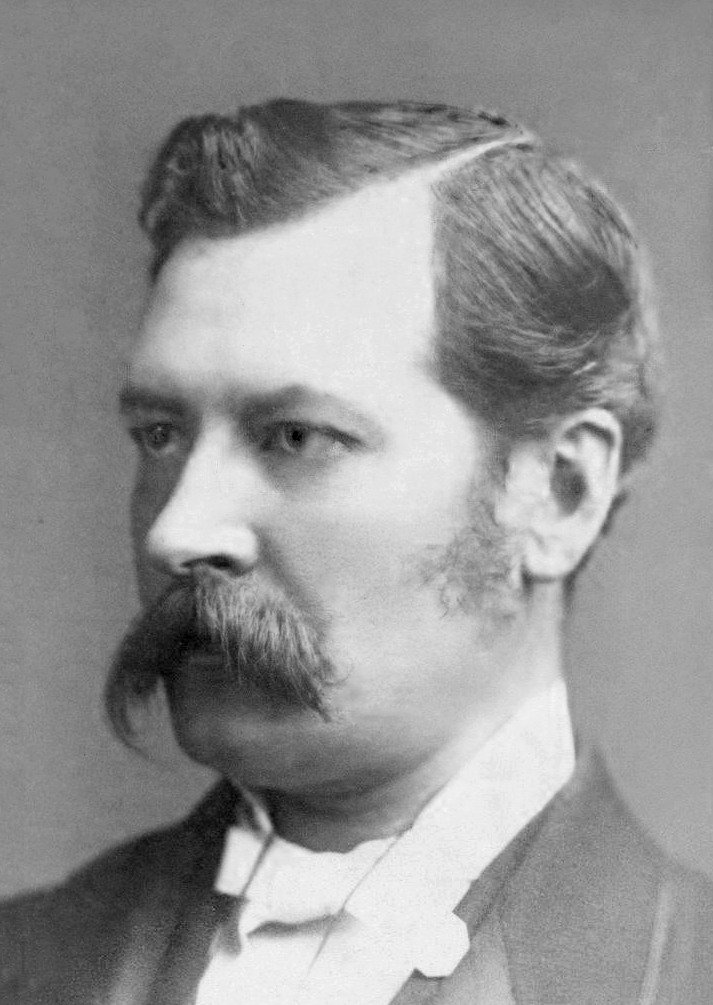

Arthur O’Shaughnessy’s name is largely forgotten, but his work continues to be a part of our cultural imagination.

Legacy of O’Shaughnessy Ode: Lingering Phrases

Despite Arthur William Edgar O’Shaughnessy slipping from collective memory, excerpts from his renowned poem, ‘Ode,’ continue to echo in our cultural consciousness.

As noted in a previous blog post, Gene Wilder’s memorable recitation of the haunting initial lines, ‘We are the music makers, / And we are the dreamers of dreams,’ in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971) lingers in popular culture. Later, Aphex Twin incorporates this unique version into the song ‘We Are the Music Makers’ on the album Selected Ambient Works 85-92.

The poem’s seventh line, ‘…we are the movers and shakers,’ still resonates in contemporary language. While the term has evolved to signify flamboyant socialites and assertive politicians, OShaughnessy initially envisioned ‘movers and shakers’ as aspiring poets shaping the world.

Read: Answering Bakhtin

O’Shaughnessy’s Timeless Verse

The poem ‘Ode,’ initially featured in the 1874 collection Music and Moonlight, remains a frequently anthologized piece, garnering early admiration from Yeats. Some critics propose that the poem not only celebrates Irish identity but also extols Irish verse. Notably, lines suggesting that a ‘new song’s measure / can trample an empire down’ align with this interpretation. In 1912, Elgar composed ‘The Music Makers,’ setting the entire poem to music for contralto or mezzo-soprano, orchestra, and chorus.

Like many ‘world-dreamers’ and ‘world-forsakers, O’Shaughnessy met an untimely demise. He contracted fatal pneumonia after catching a cold on a night out in 1881, and his life was marked by tragedy. The loss of his two children in infancy and the preceding death of his wife, Eleanor (sister of poet Philip Bourke Marston), undoubtedly contributed to the melancholic tone prevalent in his poetry.

Born in London in 1844 to Irish parents, Arthur William Edgar O’Shaughnessy faced early adversity with his father’s death in 1848. His mother found solace in the companionship of Edward Bulwer Lytton, who took a keen interest in young Arthur’s well-being. Rumors circulated suggesting O’Shaughnessy might be Lytton’s ‘natural’ son, fueled by the poet’s appointment to the British Museum in 1861 and his promotion to its Zoological Department in 1863, both endorsed by Lytton.

Dual Identity: Scientist and Poet

By day, O’Shaughnessy immersed himself in the world of entomology and herpetology, working at the British Museum. Simultaneously, he embraced his poetic inclinations during the night, indulging in the translation of French literature.

His second volume of poems, Lays Of France (1872), reimagines the twelfth-century Lais of Marie de France. Even after his death, his collection Songs of a Worker (1881) emerged, featuring translations from Paul Verlaine and Sully Prudhomme. Engaging in correspondence with Mallarmé, O’Shaughnessy demonstrated a dual identity as a scientist and a poet.

Biographer Thomas Wright describes Arthur William Edgar OShaughnessy as a delicate and ‘Dresden-china looking figure,’ typical of the brilliant young men of his time who embraced the fashion of long hair. O’Shaughnessy belonged to a social circle that included aspiring artists like poet John Payne and painter JT Nettleship.

They formed a group inspired by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, naming themselves ‘The Triumvirate.’ Playfully alluding to the PRB, their literary gatherings at the Featherstone Hotel in Southampton Row featured programs with the acronym ‘PBYOB,’ meaning ‘Please Bring Your Own Bloater.’

Networking In Pre-Raphaelite Circles

The ‘movers and shakers’ of ‘The Triumvirate’ actively engaged with established Pre-Raphaelites, frequenting parties at the London homes of Ford Madox Brown and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. They interacted with notable figures in these gatherings like American poet Joaquin Miller, the Rossettis, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and William and Jane Morris. Despite their connections, OShaughnessy faced criticism in Robert Buchanan’s 1871 essay ‘The Fleshly School of Poetry,’ where he was dismissed as a ‘second-hand Swinburne.’

Even among O’Shaughnessy’s friends, there was a perception that he did not quite measure up to the highest standards. Dante Gabriel Rossetti expressed a humorous take on O’Shaughnessy’s literary ambitions through a limerick:

There’s the Irishman Arthur O’Shaughnessy –

On the chessboard of poets a pawn is he:

Though a bishop or king

Would be rather the thing,

To the fancy of Arthur O’Shaughnessy.

O’Shaughnessy’s Discontent in the Scientific Realm

According to an apocryphal tale recounted by William Rossetti, OShaughnessy once accidentally disturbed a drawer of insect specimens. In a panicked attempt to fix the situation, he glued them back together, creating a new, mismatched species that surprised his unsuspecting boss.

Despite these unique episodes, O’Shaughnessy never truly found satisfaction in his scientific work. Richard Garnett was an exception, noting that those with poetic temperaments find fascination in ‘lizards and serpents’, despite many considering him a misfit.

The Unsettling Dichotomy: Dreamer and Specimen

Assessments from O’Shaughnessy’s friends, portraying him as a square peg in a round hole or a poor imitator, reveal a possibly unpleasant and hostile undertone. Thomas Wright’s narratives highlight the tragic and comic aspects of an aspiring poet spending days ‘among beetles stuck on pins and things in bottles.

Further, ‘O’Shaughnessy’s poems hint at a potential discomfort, idealizing the dreamer figure and anticipating a reversal of the world order, where the meek inherit the earth through the immortal power of art.

Although OShaughnessy is a minor poet, his ‘Ode’ contains a ‘deathless line’ which ensures his song endures.

Also Read: 9 questions for Bahaa Abdelmegid