Judas is perhaps one of the most notorious figures associated with suicide, comparable to Romeo and Juliet, albeit for vastly different motives. Whether from Sunday school teachings or Mel Gibson’s The Passion of The Christ, most are familiar with Judas’s infamous act of betraying Christ to the Romans in exchange for 30 pieces of silver.

In the Garden of Gethsemane, Judas addresses Christ as ‘Rabbi’ and proceeds to betray him with a kiss on the cheek, ultimately leading to his arrest by the Romans. The subsequent events in Christ’s narrative are widely familiar. However, the fate of Judas remains a topic of interest. While the traditional account suggests Judas returned the money and then hanged himself, consigned to eternal damnation in hell to suffer at the hands of Satan, the full story is more nuanced.

The Gospel of Matthew offers a straightforward description of Judas’s suicide: “And he [Judas] cast down the pieces of silver in the temple, and departed, and went and hanged himself” (Matthew 27:5). Yet, Judas’s act of betrayal and subsequent suicide stirred ongoing debate in Christian history.

Some pondered whether Judas’s role in Christ’s crucifixion was a necessary component of divine salvation. If so, why would he take his own life? Moreover, did Judas’s actions condemn him, or was his fate predetermined? Such inquiries sparked the imagination and theological musings of artists and writers throughout the Middle Ages, resulting in a rich visual tradition that employed Judas’s suicide as a means of grappling with and denouncing suicide in general, as well as Judas specifically.

The Old Testament and early Christian theology offer scant discussion on the topic of suicide. It wasn’t until St. Augustine’s influential work, City of God, that the first systematic treatise against suicide emerged, shaping subsequent theological discourse on the subject.

Arguing against a suicidal cult of martyrs taking hold of some Christian sects in the early fifth century, Augustine maintained that suicide was wrong because: 1) the commandment ‘though shall not kill’ included oneself; 2) it usurped God’s role as judge; 3) it usurped civic authority because only the law could condemn another, and; 4) it compounded sin on top of sin, as killing yourself to atone for one sin by committing another just made it two sins.

Unsurprisingly, Augustine singled out Judas as the straw man for his condemnation of suicide. He saw Judas as guilty of all of the above and that his suicide was a misguided attempt at repentance. Augustine also interpreted Judas’ suicide as an act of despair (desperatio), something counter to hope, which in his theology meant faith and belief in God.

In this respect, Judas’ suicide would become a symbol of all that was counter to Christ and the Church, and suicide in general would become synonymous with the denial of God and acts of heresy.

The earliest surviving depiction of Judas’ suicide is, interestingly, connected to the earliest surviving narrative image of the Crucifixion on an early fifth-century Italian ivory now in the British Museum (Top image: Figure 1). Made at almost the same time as Augustine condemned Judas’ suicide in City of God, the ivory shares many features that would later be elaborated upon by medieval artists.

We see Christ nailed to the cross, surrounded by the Virgin Mary, Saint John, and the centurion Longinus. Christ is not so much nailed to the cross as he stands on it, as can be seen by the position of his feet. His body is rigid and muscular. He is wide awake and triumphant, defeating death instead of succumbing to it. But Judas is just on the other side of the ivory.

His limp body is suspended off the ground, heavy enough for the tree branch to bend under his weight. The 30 pieces of silver for which he betrayed Christ lay at his feet, providing a clue as to the reason for his present state of suspension.

The ivory casket uses Judas as a direct point of contrast against Christ. If Christ symbolizes the defeat of death, Judas symbolizes death itself.

In later centuries, depictions of Judas’s suicide seethed with a vehement hatred toward their subject. One particularly striking example is the monumental sculpted capital from the Church of Saint Lazarus in Autun, France (Figure 2). Crafted around 1130, this renowned sculpture represents a significant shift in portraying Judas’s suicide.

One immediately notices the absence of Judas from the larger narrative. He is depicted in solitary agony, hanging naked and screaming from a tree. The sculpture is stark in its singular focus on the anguish and terror of the moment. Two demonic figures tug on either side of the rope constricting Judas’s neck. They throttle him with the money purse containing the thirty pieces of silver, keeping him suspended between life and death. Judas appears to acknowledge his own culpability in his predicament, mirroring the contorted faces of the demons and gesturing toward the figure on the bottom right, as if acknowledging, “I deserve this.”

If Judas’s suicide was indeed an expression of a lack of faith in God, as Augustine argued, then the logical conclusion would be that one who denied God through despair and self-inflicted death aligned themselves with the devil. This logic is precisely illustrated in this sculpture. Through such potent imagery interpreting Judas’s suicide, it’s understandable why individuals could be certain of the reasons behind his self-destruction and his ultimate fate.

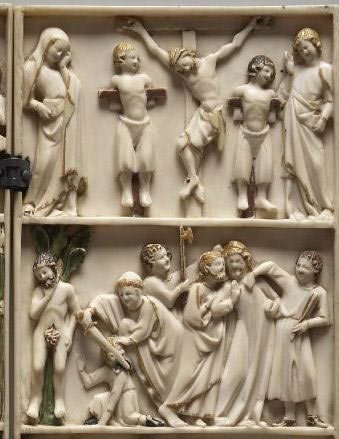

In Gothic art Judas’ suicide became grislier and grislier, with the lapsed Apostle hanging from a tree with his intestines gushing out (Figure 3). In this fourteenth-century ivory diptych from France, we see that Judas has been stripped naked, humiliated, and disemboweled.

He wraps his hand around his throat, exclaiming that he did this by himself. Unlike the sculpture at Autun, Judas is put back into the Passion story and a less abstract context. This piece is one of many gruesome depictions of Judas’ suicide in Gothic art.

The greater emphasis on Judas’ corporeal pain and his bursting body is a complex phenomenon. Although the Gospel of Matthew tells us that Judas went and hanged himself, Judas actually has two deaths in the Gospels. Judas’ ‘second death’ occurs in Acts of the Apostles (Acts 1:18), where he falls headfirst and splits open.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the two stories were combined in various ways, usually with Judas hanging from a tree with stomach bursting open as in this ivory.

Medieval literature such as Peter Comestor’s Historia scholastica and popular works such as The Golden Legend promulgated the explanation that since Judas’ mouth had touched Christ his damned soul could not escape through his lips, and thus had to find an alternative exit.

These explanations found their way into many artistic representations and were also performed in Passion Plays during Easter. The bloody spectacle of Judas’ suicide also satisfied an increasing urge to see Christ’s betrayer punished in a fitting manner. With a growing demand among worshippers in the High and Late Middle Ages for detailed depictions of the Passion and fervent devotion to Christ’s body, a concurrent emphasis on the punishment of Judas arose.

And in this world of increasing religious passion Judas’ suicide became an ever-stronger symbol of unbelievers and the gravest of sinners – heretics. It was so because if committing suicide was to despair, and despair was akin to disbelief, then suicide was the most radical expression of disbelieving. And what could be more threatening to a society built on belief than a failure to believe?

Also Read: Famous Jewish Sports Legends