Ian Walker follows the path of Ed Ruscha’s renowned photobook, “Twentysix Gasoline Stations,” tracing its steps.

We hadn’t planned to visit Williams, Arizona, but if we hadn’t, I’m uncertain if I would have penned this account. That afternoon, we journeyed from Monument Valley to the Grand Canyon, arriving much later than anticipated. After marveling at the breathtaking view, we headed to the Visitors’ Center to secure accommodations for the night, only to find no availability.

Williams, approximately 60 miles south of the Grand Canyon, appeared to be the closest motel option. So, we randomly called one, made a reservation, and drove for an hour through darkness illuminated solely by our car’s headlights.

In the bright morning sunlight, I took a stroll down the main thoroughfare of Williams—a broad street flanked by motels, eateries, and grocery stores. Throughout the street, signs proclaimed it a preserved segment of the iconic ‘Historic Route 66’. During the 1960s and 1970s, this old route had gradually been supplanted by Interstate Highway 40. Interestingly, I later learned that Williams was the final town to be bypassed by the interstate in 1984.

Despite—or perhaps because of—its discontinuation, Route 66 remains arguably the most renowned road in America. The route taken by the Joad family from Oklahoma to California in John Steinbeck’s 1939 novel, “The Grapes of Wrath,” led Steinbeck to dub it the ‘Mother Road’.

Bobby Troup’s well-known song, “Get Your Kicks on Route 66,” was recorded by Nat King Cole and the Rolling Stones, among others, while in the early 1960s, there was a popular police show on US television titled “Route 66.” It holds a mythic status and is now the subject of much nostalgia. However, as Larry McMurtry has noted, it’s important to remember that ‘it was always a dangerous road, with much more traffic than it could safely accommodate.

Sightings of dead bodies in the bar ditch and wrecked cars on tow trucks were common occurrences along old 66.’ (One of these roadside accidents was captured in a photograph by Robert Frank in 1955—a small group of bystanders huddled in a snowstorm next to a body covered in a rough blanket.)

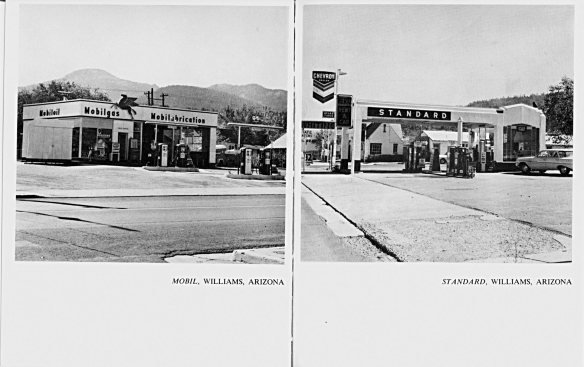

I recalled, however, that there was something else worth seeing in Williams. Walking to the end of the street, I found what I was searching for a gas station (Figure 1a). Interestingly, two gas stations were facing each other across the road—a Chevron station and a Mobil station.

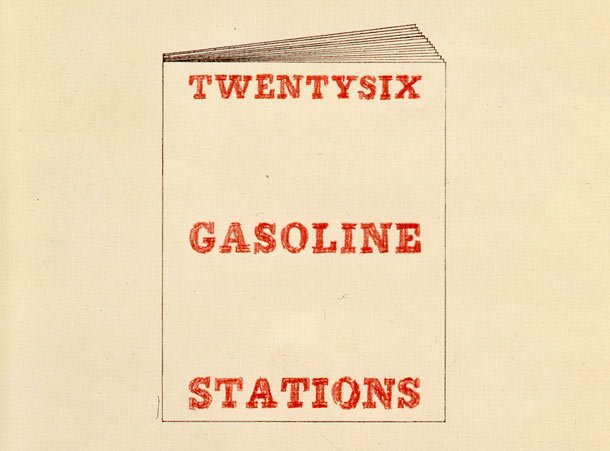

I took photographs of them because they reminded me of two other gas stations in Williams—also Chevron and Mobil—that I had previously seen in Ed Ruscha’s 1962 book, “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” (Figure 1b).

As the book’s title suggests, it features images of twenty-six gas stations captured along Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma. However, it’s important to note that the road is never depicted or mentioned in the book.

The two stations in Williams are situated opposite each other in the seventh and eighth photographs. While I couldn’t confirm if the gas stations I was observing were in the exact same locations as those Ruscha photographed in 1962 (given the rapid pace of everyday changes), my response was anything but impartial.

Also Read: Tabloid Academia

Just as my perception of Monument Valley was influenced by the films of John Ford and my perspective of the Grand Canyon was shaped by the paintings of Thomas Moran, I viewed the gas stations in Williams, Arizona, through the lens of Ed Ruscha’s photographs.

The Twentysix Gasoline Stations we encounter today are different from the book Ruscha created in 1962. Not only do they present a landscape that has since vanished, but our perception of the book has also evolved, influenced by the contextualizations and recontextualizations that have emerged around it.

Some of these interpretations are personal, such as my experience visiting Williams. Others are cultural, relating to America, the Western ethos, and the significance of automobiles. A comprehensive understanding would need to encompass all these aspects.

***

In 1962, Edward Ruscha was 25 years old. He had relocated from his hometown of Oklahoma City to attend the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1956, where he has remained based ever since. Ruscha’s artistic focus revolved around the iconic presence of ordinary everyday objects and a desire to challenge the boundaries of art.

One of the artists who greatly influenced him in this regard was Marcel Duchamp, particularly with his concept of the ‘Readymade,’ which also left a significant mark on an entire generation of artists.

In the same year that Ruscha created the book, Andy Warhol showcased his series of paintings depicting Campbell’s soup cans at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles—each being identical yet different from the others. There are clear parallels between this exhibition and “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” in their shared emphasis on everyday subject matter presented straightforwardly and repetitively. However, there is also a notable distinction: “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” is not a collection of paintings but a book of photographs.

Initially, it appeared that most viewers were genuinely perplexed by “Twentysix Gasoline Stations.” The book’s first review appeared in the Los Angeles-based magazine Artforum in September 1963. Philip Leider remarked, ‘It is perhaps unfair to write a review of a book which, by now, is probably wholly unavailable.

But the book is so curious and doomed to oblivion that there is an obligation to document its existence and record its having been there. Nonetheless, “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” surprisingly did not fade into obscurity; its reputation gradually grew.

If, back in 1963, anyone had sought to categorize “Twentysix Gasoline Stations,” it would likely have been classified as a piece of Pop Art. (Leider’s review indeed asserts this: ‘Twentysix Gasoline Stations is a Pop Art book.’) Pop Art was, after all, the latest movement in American art at the time, bridging California with New York.

In the autumn of 1963, Andy Warhol embarked on a return journey to Los Angeles, driving across the country with Gerard Malanga, Wynn Chamberlain, and Taylor Mead. Reflecting on the trip in his book “POPism,” Warhol recalled, ‘The further West we drove, the more Pop everything became … Once you “got” Pop, you could never see a sign the same way again. And once you thought Pop, you could never see America the same way again’.

In 1963, Ruscha underscored this Pop interpretation by creating one of his most iconic and precise early paintings based on a photograph of a Standard gas station in Amarillo. Transformed in this new representation, it became a kind of heroic, ideal gas station—a ‘standard’ station in the other sense. When, in 1966, the painting ‘Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas’ was featured in Lucy Lippard’s anthology on Pop Art, it was accompanied by a caption referencing the painting’s origin in “Twentysix Gasoline Stations.”

Around the same time, Ruscha received his first edition of 400 identical copies, another California artist, John Baldessari, created a series of photographs titled: ‘The backs of all the trucks passed while driving from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, California, Sunday 20 January 1963’.

It would be several years before this type of art would be categorized. In 1967, Sol LeWitt penned a brief text, ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,’ in which he defined conceptual art as follows: ‘In conceptual art, the idea or concept is the most crucial aspect of the work. When an artist employs a conceptual art form, it signifies that all the planning and decisions are made beforehand, and the execution is perfunctory.

The idea becomes the machine that creates the art.’ According to Ruscha, this is almost precisely what happened with “Twentysix Gasoline Stations”: ‘The title came before I even thought about the pictures.’

By the late 1960s, Ruscha’s books had come to occupy a central if quixotic position within Conceptual Art, though some more theoretically minded artists were skeptical of Ruscha’s attitude.

Victor Burgin later told John Roberts: ‘In that period, I remember thinking he wasn’t anybody one should take seriously. Basically, he seemed to be some sort of Californian stand-up comedian’. [13] But humor and irony were embedded elsewhere in conceptualist art and its use of photography, albeit it was necessarily of a deadpan variety.

From that point forward, any attempt to position Ruscha’s early books within art history would place them within the broad category often referred to as ‘photographic conceptualism.’

Yet, as Kevin Hatch has pointed out, any definitive effort at classification is inherently unstable: ‘Not quite Pop paintings in book form, not exactly eccentric documentary projects, and not merely a pit stop on the road to Conceptualism, Ruscha’s curious books … become increasingly difficult to categorize the more one considers them’.

This task becomes even more complex when one considers the role that “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” came to play in the discourse surrounding photography itself.

Just as the art world experienced a sudden awakening to the significance of photography in the mid-1970s, there was a simultaneous breakdown of barriers from the perspective of photography itself.

Conceptualism played a role in encouraging photographers to think more critically about the intricacies and contradictions of their medium. In 1975, Ruscha’s photographs were directly referenced in the catalog of a small yet highly influential exhibition, New Topographics, held at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York.

This exhibition marked a decisive departure from the heavy Romanticism that had characterized American landscape photography post-Ansel Adams and Minor White. For instance, the work of Robert Adams, situated around Denver, Colorado, presented an objective examination of the suburbanization of the landscape. While Adams felt anger towards the developments, his images did not overtly convey this sentiment.

Instead, he aimed to evoke a sense of calmness that he believed would ultimately have a more significant impact. He expressed elsewhere: ‘Pictures that embody this calm are not synonymous, of course, with what we might see casually out a car window. (They may, however, be more effective if we can be tricked into thinking so.)’

Adams’s comparison of the view from the car window can be intriguingly linked to Ruscha’s seemingly casual photographs. However, it is less convincing when applied to Adams’s more classically controlled work.

However, other New Topographic photographers, including Stephen Shore, directly responded to Ruscha’s work. Shore, who had worked in Warhol’s studio in the 1960s, may have had a greater affinity for avant-garde art. He first encountered Ruscha’s books in 1967 or 1968 and, as he recalls, ‘for me and my friends they were a delight’.

In 1981, the discussion surrounding “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” shifted direction with the publication of Douglas Crimp’s essay, ‘The Museum’s Old / The Library’s New Subject.’ Crimp was among a group of radical critics exploring a new concept, Postmodernism, aiming to thoroughly challenge Modernist distinctions between High and Low culture. With its diverse forms and ambiguous status, photography played a significant role in this endeavor.

In the essay, Crimp recounted an incident while conducting picture research at the New York Public Library and stumbled upon a copy of “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” filed not under ‘art’ but under ‘transportation.’ At the time, he found this amusing, but he later changed his perspective due to the considerations of Postmodernism.

Crimp remarked, ‘I now realize that Ed Ruscha’s books defy categorization within the traditional classifications of art books found in libraries, and that is part of their significance. The absence of a designated place for “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” within the current classification system indicates its radical departure from established modes of thought. This could be seen as a reclassification of “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” as ‘postmodern,’ or at least ‘proto-postmodern.’ Still, it also suggests something more elusive and fluid within the book, which consistently eludes any attempt at classification.

***

Ed Ruscha is currently regarded as a highly esteemed artist, and over time, a natural process of retrospective examination has taken place. Catalogs detailing his prints and paintings have been published, and his writings and interviews were compiled in the October book “Leave Any Information at the Signal” in 2002 (from which many of the quotations in this essay have been sourced).

The influence of Ruscha’s books has been extensively pervasive and nearly immeasurable. However, as a final note, one must acknowledge this general influence and some particular acts of homage. In 1992, Californian photographer Jeff Brouws created a small volume titled “Twentysix Abandoned Gasoline Stations,” intentionally following both the design and style of the original.

In 2008, French photographer Eric Tabuchi, in turn, paid tribute to this homage with his own collection of “Twentysix Abandoned Gasoline Stations,” featuring formal color images captured across France. In 2008, Frank Eye in England published his book “Twenty-Four Former Filling Stations,” while Peter Calvin, based in Dallas, Texas, photographed a series of 26 Repurposed Gasoline Stations, each transformed into a different type of establishment.

It is perhaps ironic that a book so seemingly simplistic and passive has generated such extensive commentary and analysis. Yet, perhaps this very simplicity allows for many interpretations to be read into it. What is truly remarkable, however, is that despite all these interpretations, the book’s ultimate enigmatic nature remains intact.

In 1973, Ruscha attempted to evoke ‘an inexplicable thing’ he was searching for and believed he had found in his books. He described it as a kind of a “Huh?”‘ – the reaction one might have when encountering the book for the first time. With this seemingly straightforward yet profoundly cryptic statement, Ruscha hinted at the resistance to categorization present in “Twentysix Gasoline Stations,” a resistance to which both Kevin Hatch and Douglas Crimp referred. Paradoxically, this resistance has allowed the book to carry numerous different meanings simultaneously.

And “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” can still evoke that unsettling effect. Even now, one might pick it up and leaf through its pages, and the only reaction that truly seems appropriate is that: Huh? ■

This article is an edited extract from our new edited collection, The Photobook: From Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond.

Ian Walker holds the Reader in the History of Photography position and serves as the Programme Leader for the MA/MFA Documentary Photography at the University of Wales, Newport. His research has extensively explored the intersection of documentary photography and Surrealism, reflected in his numerous publications. Over the past few years, he has authored two books: “City Gorged with Dreams” and “So Exotic, So Homemade.” Currently, he is engaged in collaborative work on a book focusing on Czech Surrealist photography.

Ian Walker holds the Reader in the History of Photography position and serves as the Programme Leader for the MA/MFA Documentary Photography at the University of Wales, Newport. His research has extensively explored the intersection of documentary photography and Surrealism, reflected in his numerous publications. Over the past few years, he has authored two books: “City Gorged with Dreams” and “So Exotic, So Homemade.” Currently, he is engaged in collaborative work on a book focusing on Czech Surrealist photography.

Also Read: On The Smiling Face Of Harpo Marx