Through the use of photographs and posters, Peter Collar provides a contextual analysis of Germany’s surge in racist propaganda targeting the deployment of non-European troops by France in the aftermath of World War I.

By late 1918, Germany was in a state of upheaval after enduring four prolonged years of war. The conflict had inflicted significant casualties on the frontlines, and the Allied blockade had led to increasing deprivation and hunger within the country.

Social tensions were escalating, exacerbated by the fact that the military elite had consistently assured a mostly obedient population of eventual victory until late in the war.

The reality of Germany’s actual position had now been laid bare, giving rise to a spectrum of emotions among the populace, including despair about the future, anger at the deception, and trauma over the perceived loss of lives for futile reasons.

The far-right response to Germany’s defeat involved blaming the home front and attributing the influence to the Left. While there was widespread disappointment with the terms of the Armistice, there remained a collective hope that these conditions might be alleviated through negotiations when a formal Peace Treaty was finalized.

However, this optimism transformed into anger, particularly among the Right, upon presenting non-negotiable Allied terms to the new republican Reich government. These terms included disarmament, the seizure of German colonies, the return of Alsace to France, the transfer of additional territories to Belgium and Poland, and substantial reparations.

To secure the repayment of reparations, the Allies planned to occupy the Rhineland for a period of up to 15 years.

German Resistance To The Versailles Treaty: A Battle Of Propaganda

Germany witnessed widespread protests against the imposition of the Versailles Treaty, but these efforts proved futile. Given the nation’s defenseless state and the impossibility of returning to hostilities from the German perspective, propaganda emerged as the sole viable weapon.

It was seen as a means to express defiance, persuading the international community of the injustice done to Germany and, ideally, prompting a revision of the Treaty. The occupation of the Rhineland, especially by France, was deeply resented, and matters worsened when the French incorporated colonial native troops—mainly from Africa—into their occupation armies.

For a proud European power accustomed to ruling colonial subjects seen as belonging to a lower civilization level, this deployment represented the ultimate humiliation.

Anti-Versailles Sentiments And The Pfalzzentrale

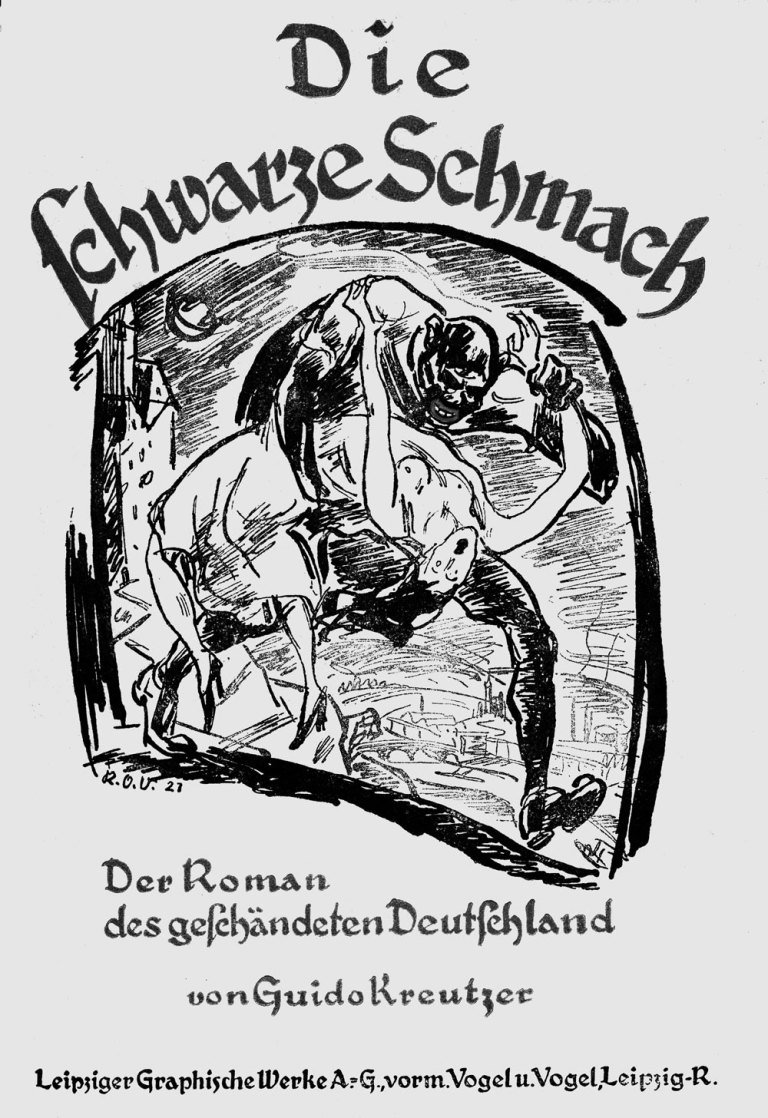

In tandem with the broader protest and propaganda against the terms of the Versailles Treaty, a harsh and venomous campaign against using colonial troops, known as Schwarze Schmach or Black Humiliation, emerged. This term, reflecting the intense emotions of those who coined it, underscored the widespread discontent. However, this issue paled compared to the more significant problem unfolding in the Rhineland.

France, driven by longstanding security interests, sought to extend its eastern frontier to the Rhine. The strategically crucial Rhineland province of Pfalz, distant from its mother state Bavaria, became a focal point.

Unable to annex Pfalz directly after hostilities due to opposition from the Allies, France attempted to sway the Pfalz population away from the German Reich, actively supporting a budding separatist movement. In response to this threat, the Bavarian government established the Pfalzzentrale, a key player in the ensuing propaganda war 1919.

Post-War Propaganda: Diverse Channels And Distorted Depictions

In the immediate post-war years, propaganda emanated from various sources, both official and private. In the absence of public broadcasts during that period, it manifested through pamphlets, posters, press articles, reports, protest meetings, films, theatrical productions, and novels.

While some propaganda aimed to maintain a relatively restrained and factual approach, a considerable portion, particularly concerning the Schwarze Schmach, shockingly exaggerated, sensationalized, and crudely executed its content. It portrayed colonial troops as untamed, brutal savages with insatiable sexual appetites.

According to the propagandists, these troops were allegedly plagued by a range of tropical diseases and, for good measure, syphilis. The portrayal depicted colonial troops as a severe threat to white European civilization, especially in the context of the birth of mixed-race children. This theme persisted into the Nazi era, leading to tragic consequences.

The Reich Interior Ministry in Berlin officially sanctioned and backed propaganda against colonial troops, albeit with materials generally falling on the less sensationalized side.

To conceal its direct involvement, the ministry operated through press offices and an agency established to preserve German culture in the occupied Rhineland.

In a similar vein, the Bavarian state government, although less restrained, found it necessary to intervene and control one organization due to “exaggerations contained in its material.”

Dynamic Individuals And Diverse Motivations

A small group of energetic individuals exerted considerable influence in Europe and America through the campaign, leaving a significant, albeit relatively brief, impact. August Ritter von Eberlein, a decorated war hero leading the Bavarian Pfalzzentrale, stood out, despite French authorities pursuing him for alleged war crimes.

Heinrich Distler, a Munich businessman with a checkered past, pursued profit through a private propaganda organization, going to great lengths to achieve his goals. In stark contrast, Otto Hartwich, the Dean of Bremen Cathedral and a conservative aligned with the old monarchist school was an honorable man who faced challenges during the Third Reich for speaking out against anti-Semitism.

Hartwich ardently campaigned against the Schwarze Schmach, reflecting European racial attitudes of the time, although his content was far from extreme. Despite their diverse backgrounds, these propagandists shared a vehement hatred for the Versailles terms, bordering on fanaticism.

While the campaign likely originated in the Reich press office with some attempted coordination, a bandwagon effect quickly emerged, allowing individuals to express their opinions freely. Protest against the Versailles terms spanned the political spectrum, with the far Right exhibiting the most extreme rhetoric. Notably, several leading propagandists, including Eberlein, later aligned themselves with the Nazi party.

Women’s Involvement In Anti-Colonial Troop Protest And Propaganda War

Women were actively engaged in the protest against the deployment of colonial troops, displaying a commitment parallel to that of their male counterparts. Organizations like the Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine, which had emerged before World War I, gained momentum during the war as women assumed supportive roles in welfare and social matters.

With their newfound enfranchisement under the Weimar constitution, women seized the opportunity to assert their voices. Simultaneously, propagandists astutely recognized the potential of depicting women as helpless, pure, and innocent victims of the alleged savagery of wild, sexually uninhibited colonial troops.

Despite the fact that French colonial troops were comparatively fewer and generally better behaved than their white counterparts, the propagandists remained undeterred in their efforts.

Women’s involvement in the protest against the use of colonial troops varied, with a more moderate approach adopted by a coalition of women’s organizations representing diverse religious, political, social, and professional interests.

Operating under the umbrella of the Rheinische Frauenliga, an agency established by the Reich government and led by Margarete Gärtner, these groups collaborated in their efforts.

On the other end of the spectrum, the more extreme stance was exemplified by the impassioned speeches of Ray Beveridge, a renegade American journalist. Known for her dramatic outbursts, Beveridge often shared the stage with August Ritter von Eberlein.

Decline Of The Campaign Against The Schwarze Schmach

The campaign against the Schwarze Schmach saw a decline after 1920-21. The Bavarian government continued to provide reduced support until the French withdrawal from the Pfalz in 1930, even though the presence of colonial troops diminished significantly after 1925.

The Pfalzzentrale considered the Ruhr crisis, passive resistance, and the resurgence of Rhineland separatism more crucial and gave them precedence.

Simultaneously, the Reich Foreign Ministry grew increasingly concerned about the French’s irritation and the resultant harm to German interests on the global stage. Consequently, it made efforts to curtail certain activities.

Discrepancies In Propaganda War And The Complex Realities Of The Weimar Republic

The crude and provocative propaganda linked to the Schwarze Schmach stood in stark contrast to the lofty ideals of the Weimar Republic. Despite proposals from liberal thinkers advocating an enlightened approach to presenting Germany’s case, their suggestions went unheeded. Various factors can be attributed to this lack of receptiveness.

Although the Weimar Republic was forward-thinking, it faced widespread unpopularity, particularly from the extreme Right, which actively sought to undermine it. Bavaria, having experienced anarchy under a communist government in 1919 and subsequent rule by social democrats followed by right-wing administrations, harbored deep-seated enmity toward a Weimar-based Reich.

Divisions within the Reich government and a largely unreformed civil service steeped in old monarchist traditions contributed to the disjointed and negative propaganda emerging from Germany in the early 1920s.

This underscores the profound societal divisions of the time and necessitates a reconsideration of how we perceive and study the rise of the Nazi Party.

Also Read: Bill Clinton’s 1992 Presidential Campaign