An epic novel of historic Palestine from the author of Time of White Horses.

Ibrahim Nasrallah’s “The Lanterns of the King of Galilee,” translated by Nancy Roberts, tells of love, loss, victory, and betrayal intricately.

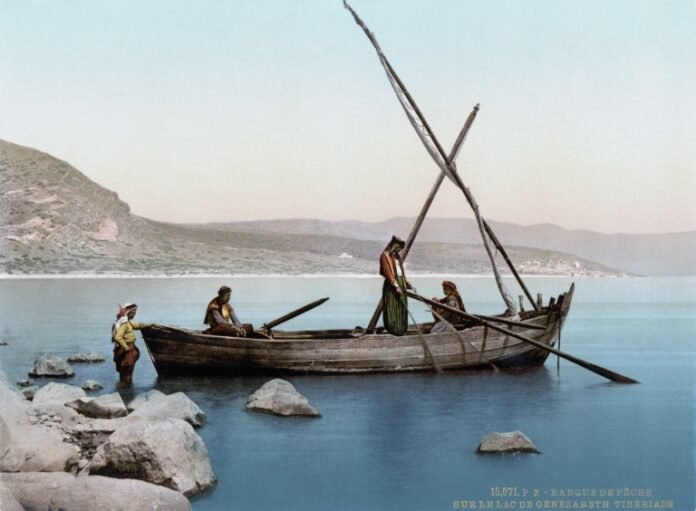

Set on Lake Tiberias, visionary Dahir al-Umar al-Zaydani aims to establish an autonomous Arab state.

Renowned poet and novelist Ibrahim Nasrallah, known for “Time of White Horses,” revives Palestinian history.

He captures a tumultuous period in the region’s rich and dramatic history using real and imagined characters.

The “The Lanterns of the King of Galilee” extract is available for reading.

A Broad Plain and Gazelles on the Run

Najma remembered the night when Umar al-Zaydani had noticed that Daher was missing. He’d inquired about Daher, but he was nowhere to be found. Then, two days later, someone had come and told him, “Someone’s seen him in Bi‘na!”

“What on earth is he doing in Bi‘na when the vizier of Sidon is besieging it?”

Three years of drought had left the plains of Bi‘na, Arraba, Jaddin, Damun, Tarshiha, and the surrounding villages nothing but colorless, lifeless expanses. The springs had dried up, and the fact that the olive trees had managed to keep their dry leaves seemed nothing short of a miracle. It was even said that if they hadn’t been described in the Qur’an as “blessed,” no leaf would have remained on their branches!

The birds had fled, and the deer that had once filled the countryside were gone, having seen the voracious looks in people’s eyes as they came after them in mad pursuit.

Even the widest and most fertile of plains, with all the verdure stored in its memory, couldn’t have endured three harsh years like these, and people longed not only for a drop of rain but for a mere drop of dew.

You may also enjoy reading: The I.B.Tauris 2016 Review – Part One

The vizier of Sidon sent word that he’d waited longer than he could afford to and that, unless they paid what they owed, he would come out with his army and collect the money due the state by force. They knew he was capable of carrying out his threat. They also knew that if he did, he would steal what remained of the meager provisions they always kept stored away for such circumstances.

During those three years, they had slaughtered most of their livestock. Some had even slaughtered their horses when they saw them on the verge of starvation.

Before the vizier’s army reached the villages near Bi‘na, news of his march on Acre, Haifa, Jaffa, Nablus, and Jerusalem had spread. As soon as they had gotten wind of the approaching storm, some of the people of Bi‘na had fled in search of safe haven, leaving their homes empty. Meanwhile, Hussein, Bi‘na’s chief elder, had set out with his townsmen and volunteers from the surrounding villages to meet the vizier’s army and block its way between Bassa and Tarshiha.

They managed to surprise the vizier’s army, which was routed and turned back. Before long, however, the routed army made a wild rush on them, displaying a strength the villagers hadn’t seen before. They retreated toward Bi‘na, which had been well fortified since the earliest times. Before reaching the town and shutting its gate securely behind them, Sheikh Hussein sent some men out asking the people of nearby villages and towns to come and help defend Bi‘na.

Meanwhile, the vizier regrouped his forces and set up camp on the Jaddin plain in preparation for a major battle.

Horror stories had come from villages in the Bekaa Valley, where homes had been looted, more than three hundred women had been raped after being chased through the orchards, and entire villages had been burned to the ground. And as if this weren’t enough, the governors and viziers had turned a blind eye to these atrocities to appease their soldiers, who were strangers in those parts.

When Daher heard Sheikh Hussein’s plea for help one day, he’d jumped on his horse and headed for Bi‘na, certain that his father had gone there before him. In fact, however, his father hadn’t heard Sheikh Hussein’s call for help until after the town was already surrounded, and by the time he attempted to reach the town, the situation of those trying to penetrate the blockade was far worse than that of the people under siege.

A solid, lasting friendship bound Umar al-Zaydani to Sheikh Hussein. Daher remembered Sheikh Hussein’s visits to them in Tiberias and his own friendship with his son Abbas, who was in love with the lake. Whenever they visited them in Tiberias, Abbas would first try to persuade his father to leave Bi‘na and come live in Tiberias.

Sheikh Hussein would laugh and say, “Leave Bi‘na? That would be difficult, Abbas! But if it’s all right with Sheikh Umar, you can spend the week here with your friend.”

Sheikh Umar would welcome the idea every time. Then one week would stretch into two, especially in the winter, since Daher would always argue his case, saying, “What’s Abbas going to do with himself there in Galilee’s cold?”

Abbas was keen on fishing, but Daher loved to hunt ducks on dry land.

As he reflected on those days, he could see Abbas’s face and hear Sheikh Hussein’s resounding, jolly laugh – a belly laugh that came from the heart and diffused through the air. Daher had never heard one like it before. Of all the men Daher had ever known or would ever come to know, Sheikh Hussein was the only one who could infect others with such joy that all the men near him were either smiling or laughing as though they were discovering their hearts for the first time.

Whoever came out of his diwan laughing would say loudly, “O God, let it bring good!” This was because they were afraid of laughter, and when they caught themselves laughing so much they saw it as an evil omen. It was as though they thought their share of this world was nothing but sorrow.

Daher reached Bi‘na’s gate shortly before midafternoon. Gazing out at the short, skinny boy, the men stationed along its wall asked him his name. “Daher,” he replied. When they asked him about his acquaintances in Bi‘na, he said, “Abbas.” “Abbas who?” they asked. “Abbas the son of Sheikh Hussein,” he said, surprised. “So what brings you here?” they wanted to know.

“I want to fight with you,” Daher replied.

“Whose son are you?”

“I’m Daher al-Umar al-Zaydani.”

“Go back to your family, son. You’ll be of more use to them there than you’ll be to us here.”

Just then the men on the wall shouted, “The army’s arrived!”

Chaos broke out, and they scrambled to secure the gate with more wooden beams.

The angry vizier had given them no forewarning. He’d made his decision to bring the town down on their heads.

He set up his cannons and began pounding the town with shells.

Night fell, and his cannons carried on with their work with such intensity that the residents of Acre, eighteen kilometers to the west, could hear the explosions quite clearly.

The following day, the bombardment continued, but the town’s walls stood firm to everyone’s amazement. By the seventh day, the vizier realized he would need more shells, so he sent people to bring some from Sidon.

As for those inside, they realized that the vizier, who hadn’t given them a chance to fire a single bullet or shoot a single arrow in the direction of his forces, wouldn’t retreat until he had leveled their town to the ground.

Behind the army, the vizier set up a huge, gaudy pavilion which, in its peacock-like pomposity, was alien to everything on the surrounding plain. He spent the day issuing orders to kill all the fleeing villagers his soldiers brought him.

He asked them all a single question: “Are you going to pay the taxes you owe?”

Of course, he had no need to ask such a question as he sat looking at their emaciated frames and tattered garb.

At a nod of his head, the soldiers would lead the villagers away from the tents and, next to a low stone wall that surrounded one of the lifeless orchards, shoot them dead.

The Lanterns of the King of Galilee is out now

Ibrahim Nasrallah, born to Palestinian parents in Jordan in 1954 and raised in a refugee camp, has authored fourteen poetry collections, fourteen novels, and works of literary criticism. Additionally, he is a painter and photographer. Nasrallah is known for his works, such as “Inside the Night” (AUC Press, 2007) and “Time of White Horses” (AUC Press, 2012).

Nancy Roberts, a translator of Arabic novels, received recognition in the Saif Ghobash-Banipal Prize for Translation for her work on Salwa Bakr’s “The Man from Bashmour” (AUC Press, 2007). She has also translated Ibrahim Nasrallah’s “Time of White Horses.”