In the last thirty years of his life, Leo Tolstoy developed a moral philosophy that embraced, amongst other things, vegetarianism. But how did Tolstoy’s stance compare to the wider vegetarian movement of the late-nineteenth century?

During the late nineteenth century, there was a growing organization within the vegetarian movement. The inception of the first vegetarian society occurred in Manchester in 1849, followed by the establishment of an American counterpart in 1850 and a German society in 1867. This movement gained prominence through its publications, guides, and culinary resources, as well as the emergence of vegetarian eateries across European cities. Harold Williams, a novice traveler from New Zealand during the 1890s, found himself dining at vegetarian restaurants not only in London and Berlin but also in Derby.

The arguments supporting vegetarianism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were diverse, with origins spanning various concerns. Some arguments were based on pseudo-scientific health claims, while others emphasized animal rights and humanitarian principles. Advocates contended that vegetable-based diets were hygienic and purifying, contrasting meat consumption, which was perceived as containing toxins and waste material. They argued that meat, being the flesh of deceased animals, harbored undesirable substances like sweat, nitrogenous waste, and decay remnants. Additionally, meat was deemed unnatural for humans; if it were natural, wouldn’t people consume it raw like vegetables? Even Edward VII’s bout of appendicitis, delaying his coronation from June to August 1902, was attributed to his meat-heavy diet rather than vegetarianism.

Critics of vegetarianism often criticized the perceived lack of nutritional value in vegetarian diets. However, vegetarian advocates countered by highlighting the diversity of vegetarian cuisine and the physical prowess of vegetarians in sports. Despite their minority status, vegetarians were noted for achieving athletic honors in walking, racket sports, and cycling competitions. Furthermore, it was observed that the strongest (such as horses, oxen, and camels), fastest (like antelopes and hares), longest-lived (such as elephants), and most intelligent (including elephants and apes) animals were herbivores.

The ethical concerns surrounding the slaughter of animals for food, including the methods employed, were key arguments within the vegetarian movement. Additionally, attention was drawn to the harsh conditions endured by workers in the meat industry, such as butchers, slaughtermen, shepherds, and drovers. Some vegetarians objected to the exploitation of animals as labor, citing instances of mistreatment, cruelty, excessive workload, and negligence. Moreover, they opposed the use of animals for entertainment purposes, such as hunting, shooting, dog-fighting, or rat-worrying. While not all vegetarians agreed, some argued for consistency by abstaining from leather footwear, advocating instead for going barefoot to avoid confining the foot in uncomfortable and unventilated shoes described as “stiff, foul, unventilated prisons.”

However, finding a practical alternative to leather proved challenging. In a competition held in 1895 to discover the most suitable pair of vegetarian shoes or boots, judges concluded that none of the submissions fully met expectations. One individual expressed these concerns, along with critiques of the construction of late nineteenth-century footwear, through a poem published in The Vegetarian.

“Father,” I spoke as my dad glanced up from his work, “Why do I appear downcast amidst a crowd of cheerful faces? It’s as if my spirit is withering from within.”

“You seem troubled, my son,” he remarked.

“Yes,” I replied, “You’ve pinpointed it. It’s the boots—the Vegetarian boots.”

“I will not make a pig squeak or a great ox moan. I will never, ever eat a chop or pick a mutton bone.”

My sect, which survives on bread and fruit, is growing quickly these days, but what good are we if we don’t wear vegetarian shoes?

“We’re informed that leather comes from hides, which merely conceal flesh. Therefore, if we continue to wear leather shoes, does it truly matter what we consume? The rubber soles may be practical but often attract unwelcome attention. Oh father, where can I find a pair of Vegetarian boots?”

“Ahem,” my father cleared his throat, “Though my dietary choices differ from yours, and I hold steadfast to my beliefs even in the face of opposition. Take solace in your uncomplicated nature, satisfied with nuts and fruits. As for me, I have a secret to share concerning ‘Vegetarian boots’.”

“There was a time when leather footwear was ubiquitous, but now, with the advent of ‘patent’ shoes, we consume leather, labeling it as ‘beef’ or whatever suits our fancy. I’ve transitioned to using brown paper, a material devoid of animal origin, in my creations. Consequently, anyone who purchases my products dons Vegetarian boots.”

Vegetarians embraced a broad reformist perspective, forging connections with various other movements. While closely aligned with temperance, animal rights, and anti-vivisection movements in terms of ideology and social ties, vegetarianism also found associations with a range of unconventional beliefs and practices. Vegetarians were often associated with diverse ideologies, such as alternative views on economics, participation in organizations like the Society for Psychical Research, preference for all-wool clothing, abandonment of shaving, and adoption of unconventional headwear.

Moreover, vegetarians played active roles in the establishment of reformist groups like the Humanitarian League in Britain, which aimed to unite reformers under a common principle of compassion, and the League for Total Abstention in the Netherlands. The Bulgarian Vegetarian Union pursued ambitions beyond dietary concerns, seeking to elevate the moral, intellectual, and physical well-being of its members.

Leo Tolstoy emerged as a prominent figure in the nineteenth-century vegetarian movement. His essay “The First Step” gained widespread promotion by vegetarian societies worldwide, and his writings, spanning topics beyond diet, were featured in vegetarian publications. Tolstoy’s adoption of vegetarianism was just one facet of the Christian anarchist philosophy he developed later in life. This philosophy encompassed principles such as temperance, chastity, rejection of private property and money, and an absolute aversion to violence or coercion.

The extensive scope of Tolstoy’s interests led his followers to engage with various reformist movements during the 1890s, with vegetarianism being just one of them. Tolstoyans collaborated with the vegetarian movement, sharing platforms and speakers. Vegetarian eateries served as physical gathering spaces for them, whether it was the Vegetarian Cooperative Association in Sofia, the Pomona vegetarian hotel and restaurant in The Hague, or the Central Vegetarian Restaurant in London.

Visitors to Tolstoyan communities, like the one in Purleigh, Essex, noted the absence of deprivation in the vegetarian diet. During the centenary celebrations of Tolstoy’s birth in Moscow in 1928, individuals like Charles Daniel enjoyed vegetarian fare at the Moscow Vegetarian Society’s restaurant. Edith Crosby recounted a lavish vegetarian meal shared with Tolstoyans, including Chertkov, describing a menu replete with omelette, macaroni, vegetables, fruits, dessert, salad, and cheese, highlighting the Tolstoyans’ culinary prowess compared to religious groups with more austere dietary practices.

While Tolstoy and his followers drew upon arguments from the broader vegetarian movement, they placed particular emphasis on issues related to violence against animals and humanity. Tolstoyans explicitly linked vegetarianism to a broader humanitarian ethos, advocating for the deepening of compassionate values that underlie vegetarianism and their application across all aspects of human behavior. Vladimir Chertkov, Tolstoy’s close associate residing in England during the 1890s, urged the vegetarian society to not merely advocate for the spread of vegetarianism but to foster a more profound sense of compassion that extends to all facets of consciousness and conduct.

Chertkov questioned how one could condemn the killing of animals for food while remaining indifferent to the violence of warfare and capital punishment. While not universally accepted within the vegetarian movement, Tolstoyans viewed vegetarianism as a component of a comprehensive worldview. They distinguished themselves from animal rights activists by eschewing legislative approaches or punitive measures for animal mistreatment. Instead, they advocated for the cultivation of empathy and humanitarianism among individuals involved. Non-violence, non-resistance, and brotherhood formed the foundational principles of Tolstoyan vegetarianism. While these principles fostered close cooperation with vegetarians, they also set Tolstoyans apart in many respects.

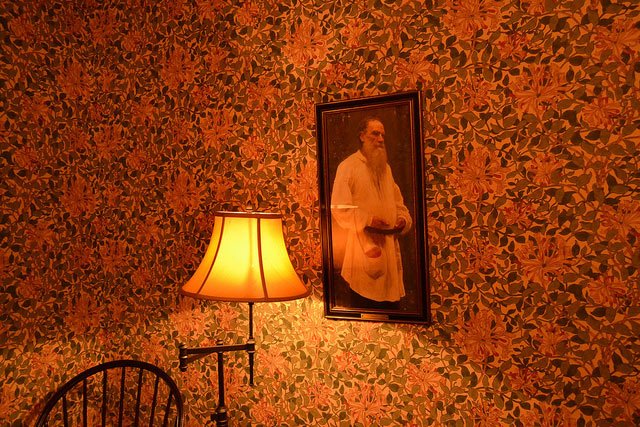

Image courtesy of ptwo.

Charlotte Alston’s new book is Tolstoy and his Disciples: The History of a Radical International Movement. Senior Lecturer in History at Northumbria University, her other books include Russia’s Greatest Enemy: Harold Williams and the Russian Revolutions.

Charlotte Alston’s new book is Tolstoy and his Disciples: The History of a Radical International Movement. Senior Lecturer in History at Northumbria University, her other books include Russia’s Greatest Enemy: Harold Williams and the Russian Revolutions.