We’re delighted to announce that Leon McCarron has received the 2017 Neville Shulman Award, which aims to further the understanding and exploration of the planet: its cultures, peoples, and environments while promoting personal development through the intellectual or physical challenges involved in undertaking the research and/or expedition.

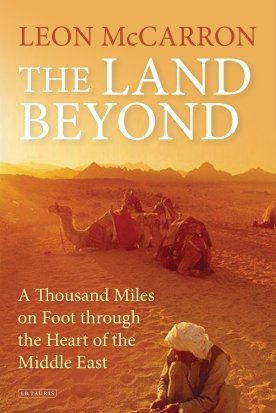

To celebrate, we’re running an exclusive extract from McCarron’s forthcoming The Land Beyond, which follows him along a series of wild hiking trails that trace ancient trading and pilgrimage routes and traverse some of the most contested landscapes in the world to Jordan and the deserts of the Sinai.

It is a pilgrimage that takes him back through time, from the quagmire of current geopolitics to the original ideals of faithful men, and along the way, looks at the many layers of history, culture, and religion that have shaped the Holy Land…

Towering above Nablus is Gerizim, one of the two mountains that enclose the city, and the summit is home to the world’s smallest and oldest ethno-religious sect: The Samaritans.

They are the remnants of an ancient people and can trace their roots back 127 generations through the Holy Land; in a land dominated by the monotheistic trinity of Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, the Samaritans are a fourth, distinct Abrahamic faith, living out a unique and harmonious relationship with their neighbors.

They claim to be descended from two of the Twelve Tribes of Israel – Menashe and Ephraim, dating them to the 7th Century BC – and at one point during Roman times their members numbered well over a million. Today, the Samaritan population is registered as just 777 people.

Kiryat Luza is a gated community that is both physically and politically separated from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and amongst ethnic and religious divisions around them, the Samaritans stand alone as impartial and unaffiliated.

They share many commonalities with their Jewish neighbors, as far as celebrating the seven festivals mentioned in the Torah and following the Five Books of Moses. Culturally, however, given their geographical location, the Samaritans in Kiryat Luza are closer to the Arabs; many works in Palestinian offices in Nablus and beyond, use the Palestinian school system and speak a local Arabic dialect. However, the Samaritans categorically refuse to associate with either ‘side’ in the geopolitical divide.

They are well-liked by both communities, carry Israeli passports and Palestinian ID cards (and occasionally Jordanian passports, too), and often have a confusing but rather wonderful cross-pollination of names: Anwar Cohen, for example.

I went to visit the Samaritans of Kiryat Luza alone. Outside the hotel I looked for a taxi and instead found a man called Majdi lurking by the entrance. He was very short with slicked-back hair and a sideways smile. His shoulders were permanently hunched: he looked like a Hollywood casting agent’s impression of a 1980s Italian mobster.

Majdi said that Kiryat Luza would be closed to visitors at that time of the evening but that he knew the Samaritans well. He could get me in if a few dollars were in it for his trouble. He called a friend who arrived in a yellow taxi, and we set off up a long winding hill, climbing high above the city until the lights of Nablus spread out beneath us like a blanket.

We parked in the village and I followed Majdi down a wide, quiet street. He opened a door, and we walked up some stairs in darkness, through a glass door, and into an office. A priest sat behind a computer, tapping away furiously at the keyboard.

He wore a grey tunic and had a thick ashen beard. His head was covered by a heavy-knit and very un-cleric-like woolen hat with a bobble. “This is Mr. Husney Cohen,” said Majdi. “He’s a very important Samaritan Priest, and he runs the museum. He knows more about the Samaritans than anyone else.”

Mr. Husney Cohen did a great job of ignoring me and complained to Majdi that he shouldn’t bring people to the village, especially late at night. It took five more minutes of typing before he even looked at me. “Don’t film me here,” he said. I causally lowered my camera, which had been recording everything. “What are you writing?” I asked.

“I’m writing a Facebook post, and it’s very important. That’s why I didn’t want to be interrupted. I have a new theory.”

“What is it?” I asked.

“That the original woman, Eve, caused all of the problems we have in the world right now,” he said sternly. Then, with a smile, he added, “her and the Arabs.” He winked at Majdi and they both laughed. Until now I hadn’t noticed how close the two men were, but the joke showed affection underneath Husney’s grumpiness.

He tore himself away from Facebook, changed into a smart red Priestly cap, and we walked down the street to a large locked wooden door. Inside we would find the Samaritan Museum. A small sign read ‘Samaritan Museum’ by the door – otherwise, in the fading light of evening, it looked just like anywhere else in the quiet, ghostly town.

Husney switched on the lights inside. “Okay,” he said. “This is the history of the Samaritans. Please listen.”

For the next hour, he spoke to me almost non-stop. It was a tour-de-force: performance, part history lesson, part sermon. He traced his lineage to Moses and pointed to a chart proving the bloodline. He held up some family trees and pictures of previous High Priests. Oil paintings of Romans and men in loincloths on mountaintops were pointed to, and I was told to write everything down. The schism with Judaism, he said, came early. “We are not Jews,” he reminded me more than once.

Jews believe that Jerusalem was the location of God’s commandment to Moses to kill his son, Isaac. The Samaritans know the real site to be Mount Gerizim. There were some artifacts and a few barbed digs at the other religions. There were a lot of maps and a small amount of singing. His phone rang regularly, and he would answer, chastise the person at the other end, and continue with his encyclopedic lecture on Samaritan culture.

Mark Twain also met the Samaritans. ‘Talk of family and old descent!’ he writes. ‘The Samaritans could…name their fathers straight back without a flaw.’ It was quite something, now as then, and Husney was rather enjoying himself. I was shown a copy of the Ten Commandments of the Samaritans, which are different from the Christian and Jewish decrees in that they dictate the sanctity of Mount Gerizim. Finally, I was treated to a lengthy chant in Ancient Hebrew while Husney stared trance-like at a leather-bound, very old-looking copy of the Torah, which had been carefully placed on a red felt altar. I felt like I had, very briefly, entered another world.

Leon McCarron, winner of the Neville Shulman Challenge Award 2017, is an adventurer and filmmaker specializing in long-distance, human-powered expeditions. In recent years, he has cycled worldwide, walked 3,000 miles across China, and trekked 1,000 miles through the Empty Quarter. He is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He has released an award-winning independent film, Into the Empty Quarter, and his ship’s four-part TV series, WalkingHomefrom Mongolia, for National Geographic. A third lm, ‘The Last Explorers on the Rio Santa Cruz’, is due out in April 2017. Visit Leon McCarron’s website here.

Also, Check out: ‘Egypt had the longest hours in the world’ – André Aciman’s Alexandrian awakening