As a youth, I maintained a diary, and on Monday, February 13, 1978, I penned a tale featuring Batman. It might not have been my initial Batman story, but it certainly wasn’t the final one.

Unfortunately, I can no longer access that diary, but that’s inconsequential. Thanks to Google Books, I can effortlessly locate my story online within moments.

Ph.D. Journey and Book Creation

Commencing my PhD in 1996, I didn’t envision it becoming a book. Crafted over three years and spanning 103,000 words, it was initially for my supervisors and possibly myself.

Fearing it might be my last extensive piece, I infused it with various aspects of my personality – both arrogant and pretentious. Released as “Batman Unmasked” in the early 2000s, it marked a significant milestone.

You may also like: The Universe of Satyajit Ray

Reflecting On Batman And Personal Growth

In 2005, I received a request from Alan McKee to revisit Batman for his work, “Beautiful Things in Popular Culture.” Once again, I intertwined reflections of Batman with personal anecdotes:

You form a bond with a man, an elder companion, over a span of three years. People naturally inquire about his well-being when they encounter you, considering you a pair, your names often mentioned together.

Eventually, the relationship gently fades away, leaving a sense of closure. You remove his photos from your wall, stow away mementos, and move on.

Occasionally, you hear updates about him – a makeover, a new partner, or a rekindled romance. You offer him your best wishes. Then, unexpectedly, you’re asked to single out the pinnacle moment, the finest adventure, or the most remarkable day.

To me, it extends beyond comics, films, and television; it embodies a significant phase of my life from 1996 to 1999.

During that time, I resided in a tiny Cardiff apartment resembling a monk’s cell, with a shower tucked in a cupboard next to the kitchen sink and a bathroom confined to a dank cubicle.

The walls were adorned with images of my chosen icon, Batman, and shelves laden with graphic novels; I embraced my identity as Doctor Batman, a label bestowed upon me by tabloids when they uncovered my Ph.D. research in the spring of ’99.

For me, Batman is a visual narrative, a photo album capturing moments from 60 years – a flick-book of images, each possessing its unique charm and evoking a rush of memories.

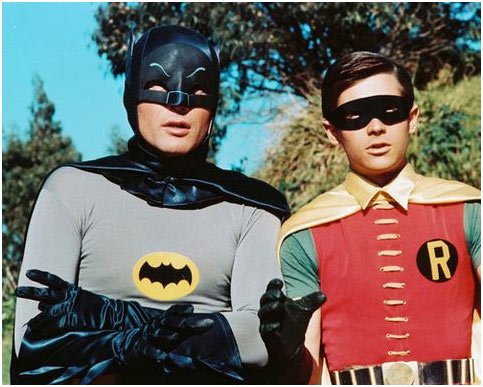

From the ‘Negative Batman’ of the 1970s to the heroic Adam West Batman of my childhood, the feverish dreams induced by Denny O’Neil’s ‘Shaman’ Batman during a week of flu, the stark brutality of the first late-’30s episodes, to Grant Morrison’s scar-hardened Justice League Batman, and the stylized Expressionist Batman of the animated TV series gliding gracefully across the city – each portrayal weaves into the rich tapestry of my experiences.

Around 2008, I revisited Batman deliberately, avoiding revisiting my earlier work or injecting too much of myself into the writing. I believed the world had seen enough of my diaries. In “Hunting the Dark Knight,” I explore this character as both myth and mosaic.

Batman As A Mosaic Icon: Embracing Diversity And Complexity

Batman operates as Gotham City’s crime-fighter, relying on intellect, physical prowess, wealth, and ingenuity, devoid of superpowers. This foundational framework accommodates interpretations like Frank Miller’s, Joel Schumacher’s, Bob Kane’s, and Adam West’s Batman. The character encompasses contradictions, being both ridiculous and fearsome, a fatherly protector, a big boy scout, a grim vigilante, and a gothic guardian.

Each narrative contributes to the archetype, building a multifaceted, partly shared, and partly individual sense of Batman. The mosaic icon is an evolving collage belonging to all who contribute to its construction, capturing light differently from various angles.

Evolution Of Personal Perspective: Embracing Batman’s Complexity Over Time

Over my sixteen-year PhD journey, my admiration for

Batman has grown from Miller’s gruff commander to embracing diverse versions. Initially drawn to the agile figure, my preference evolved with age, identifying with Robin and appreciating Batman’s flaws. As time passed, even his silly moments contributed to a deep love for the character in all his variations.

Despite attempting to avoid personal elements, questions about my favorite Batman and ownership of the costume persist in real-life and online interactions. These inquiries are interlinked, reflecting the fusion of my scholarly exploration and personal connection with the iconic superhero.

I appreciate the fact that you’re a fan of Batman.

Batman’s Allure Embracing Versatility And Humanity

The fascination with Batman transcends mere entertainment, encompassing his adaptability to different roles while upholding a consistent set of values. His uniqueness lies in being a man who willingly adopts the persona of a bat, diverging from superheroes with supernatural origins. Despite lacking superhuman abilities, Batman’s tenacity, intellect, and intense training enable him to stand alongside god-like counterparts, epitomized in his ability to confront even formidable figures like Superman.

Batman As A Symbol Of Human Potential

It symbolizes a plausible fantasy of human potential achievable through hard work, education, and dedicated training. This contrasts with superheroes possessing extraordinary origins, as Bruce Wayne’s wealth, intelligence, and athleticism present a fantasy within reach, albeit under distinctive circumstances.

This perspective explains the preference for portrayals emphasizing Batman’s humanity, such as Miller’s Year One, showcasing relatable mistakes and a more average physique.

Nolan’s Batman and Obscure Takes

Christopher Nolan’s depiction of Batman, crafting his weapons and costume, invites viewers to share the fantasy of achieving similar feats with the right resources. Similarly, the appeal extends to lesser-known versions like those from Gotham By Gaslight (1989) and Batman Year 100 (2006).

These Batmen, with chunky and pieced-together costumes, evoke simplicity and accessibility, making them relatable and conceivable for the everyday person.

A Personal Journey Into The Batman Mythos

Reflecting on my own connection with Batman during the final months of my PhD, I immersed myself in the myth of a man who dresses as a bat to fight crime. While I didn’t own a costume, I embraced elements of his attire during feverish dreams of shamans and totems. This period of academic intensity led to nights exploring the city with a coat, boots, and leather gloves, embracing the allure of Batman’s world.