The featured painting of the week 38 is Lyonel Feininger’s “The White Man,” created in 1907. It is an oil on canvas piece measuring 68.3 x 52.3 cm and belongs to the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, currently on deposit at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Upon arriving in Paris in July 1906, Lyonel Feininger, who had previously worked as a caricaturist for several satirical German magazines, naturally found himself drawn to literary and journalistic circles.

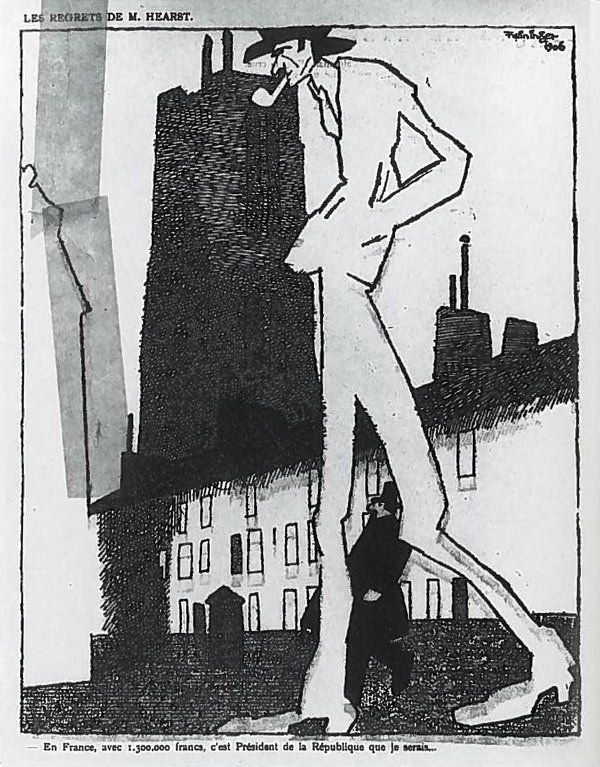

He contributed illustrations to various Parisian magazines, including the journal Le Témoin. One of these illustrations, sharing the same composition as the painting mentioned above, was published as a cartoon in 1906 titled “Les regrets de M.Hearst” (Fig. 1).

Interpretations of the subject matter in both the caricature and the painting have varied significantly, particularly regarding the identity of the “white man.” The cartoon’s title, “Les regrets de M.Hearst…” and its accompanying caption, “In France with 1,300,000 francs I could be president of the Republic,” were likely provided by the journal’s editor rather than the artist himself.

Also Read: Painting Of The Week: 99

To Feininger’s contemporaries in Paris, the tall figure in the white suit, hat, and pipe might have evoked an American newspaper tycoon. However, it is clear that the image did not intend to portray William Randolph Hearst, nor did it necessarily represent an American figure at all.

Interpretation Of “The White Man” By Lyonel Feininger

Analysis by Alois Schardt, who interpreted the figure as a traveling Englishman, sheds light on the compositional aspects of the painting of week 38 “The White Man.” According to Schardt, one notable aspect of the artwork is the noticeable difference in scale between the main figure and the surrounding architecture.

The man depicted in the painting appears larger than life, extending beyond the confines of the picture frame and seemingly transcending its boundaries into the infinite space beyond.

This was evidently an intentional technique used to achieve a particular objective. In a letter dated 1906, Feininger wrote:

Subtle variations in relative proportions result in significant disparities in the grandeur and intensity of the composition. Feininger argues that monumentality is not achieved merely by enlarging objects, which he deems simplistic. Instead, it involves juxtaposing large and small elements within the same composition. He suggests that something monumental can be depicted on a small scale, while even extensive canvas can be underutilized if not approached thoughtfully.

Interpreting “The White Man”: Varied Perspectives And Speculations

In contrast, Hans Hess, who wrote about Feininger’s life, suggested that “The White Man” represented the artist himself. Hess described Feininger as a tall, awkward figure, likening him to the character depicted in the painting: “There he stands, as tall as the Tour St Jacques, hands in his pockets, an American in Paris.”

This interpretation seems plausible when considering Feininger’s self-portrait published in the Chicago Sunday Tribune on April 29, 1906, where one can discern similarities in the depiction of the “white man,” characterized by spindly legs and large feet. (Fig 2)

Ulrich Luckhardt, a recent author who has extensively studied Feininger’s work, suggests that while the figure in the painting “The White Man” shares similarities with the artist’s caricatures and may evoke associations with certain personal snapshots, it lacks a specific reference.

For example, Luckhardt points to an old family photograph from 1905 depicting Feininger on a beach at Graal, which resembles the figure’s pose in the 1907 painting. However, Luckhardt views the “white man” portrayal as more abstract and unrelated to any particular individual or event.

A Critical Oversight In Interpreting Feininger’s ‘The White Man’

Despite extensively focusing on deciphering the meaning behind the figure of the ‘white man’ in Feininger’s painting of week 38, scholars have paid little attention to the significance of the ‘black man.’ Given their relative proportions within the composition, this oversight is understandable.

However, when considering the historical context and the artist’s potential self-portrait, the ‘black man’ could represent an alter ego, embodying the darker, more sinister aspects of Feininger’s psyche.

In this interpretation, rooted in the time and urban setting of Freudian theory and the early 20th century, the ‘black man’ may symbolize a sabotaging force, hindering the progress of the purposeful ‘white man’.

It is as though this darker aspect of the artist’s personality is constantly undermining his efforts, diverting him from his true objectives. In this light, the ‘black man’ takes on a pesky, distracting quality, complicating the narrative of the painting and offering a deeper psychological dimension to Feininger’s self-portrait.

Also Read: Painting Of The Week: 89