Lilian May Miller, born in 1895 in Japan to an American diplomat, spent her youth there. Later, her family moved to Washington, and she attended Vassar. After graduation, she lived in Tokyo and Korea, gaining success as a woodcut artist.

During World War II, Lilian May Miller resided in Hawaii and succumbed to cancer in 1943. Despite achieving some fame, her untimely death and the destruction of her works post-Pearl Harbor contributed to her relative obscurity today.

Lilian May Miller, an artist and poet, navigated the complexities of east-west and tradition-modernity in her life. Her unique choices make her a compelling subject for study.

Also Read: Floods in Bosnia create new landmine risk

Cultural Borrowing

Lilian May Miller, enrolled in Kano Tomonobu’s private atelier at age 9, displayed early talent. Still, her entry into art at a young age raises questions about it being a genuine career choice.

Unlike some female artists labeled as ‘rebels,’ Lilian May Miller followed her father’s wishes, prompting scrutiny of her Orientalist stance. David Bate highlights the historical Occident-East relation, emphasizing how imitation disrupts authenticity and acknowledges the East entering the West.

Lilian May Miller’s identity grapples with the tension between colonizing Japanese culture and being colonized by it. The demand for Oriental images in Europe and America was fueled by writers like Edmond de Goncourt, who introduced Japanese art appreciation.

Goncourt and his brother identified Japonisme as a cultural movement, underscoring their role in creating and popularizing this phenomenon.

Ukiyo-e prints from 18th-19th century Japan lacked local value. Artists like Hokusai gained fame in the West.

Western women Helen Hyde and Bertha Lum embraced ‘shin-hanga’ in Japan. Miller, born in Asia, stood out.

Examining their lives challenges Said’s Orientalism and Reina Lewis’s gender theories. Brown questions if their unconventional lives oppose patriarchal Orientalism values.

Miller entered a changing art scene. Japanese artists fused tradition with modernity in Sosaku Hanga technique. It was influenced by European methods.

Independent Woodblock Printing Of Lilian May Miller : Challenging Tradition

Traditionally, craftsmen executed woodblock prints under an artist’s guidance. Miller, in contrast, handled the process independently—cutting woodblocks and printing colors herself.

In Japan, Lilian May Miller, a foreigner, preserved traditional art. In America, she conveyed Asia’s beauty. Adopting a ‘Japanese’ identity, she became part of an Oriental tableau in gallery displays.

Miller’s ‘Japanese’ identity extended to attire, often wearing a kimono. Joan Jensen suggests ethnic cross-dressing may signal solidarity or question one’s ethnic identity.

Residing in Japan during the 1920s, Miller’s kimono served as a visual cue, hinting at a complete immersion in Japanese style at ‘home.’ Adopting another culture raises questions about cultural assimilation.

Marie Antoinette’s shepherdess attire distanced her from the subaltern, emphasizing her non-shepherdess identity. Miller adopted Japanese attire with a close affinity for Japanese life, blurring the lines between appropriation and personal taste.

Comfort in Tradition: Lilian May Miller’s Connection

Growing up in Japan, Miller viewed Japanese costumes differently than her observers. The kimono, not ‘foreign,’ symbolized familiarity and foreignness to American audiences.

Alys Eve Weinbaum analyzes 1920s American fashion ads for ethnic-themed clothing. Consumers sought a cosmopolitan look, distancing from racial ‘otherness,’ rather than aspiring to become Asian or ‘primitive.’

Richard Serrano sees cultural borrowing as a modernity badge. Critiques of ‘voice appropriation’ challenge borrowing’s harm to the culture and question its association with modernity.

Lilian May Miller unique background distinguishes her from other Orientalist artists. Unlike them, Asia wasn’t a personal discovery for her; it grew from her father’s interests. Her poetry doesn’t parallel Ezra Pound’s ‘creation’ of Chinese poetry in English. However, she contributed to perpetuating an essentialized Orient in the Western collective mind.

Contrary to many Orientalist artists rejecting parental and societal values, Miller’s project aligned with her father’s interests. Her prints, often greeting cards for expatriates in Asia, financially benefited from multiple originals in woodblock printing. As Brown asserted, transitioning from pen and ink to woodblock prints was primarily driven by financial considerations.

Transcending Boundaries: Lilian Miller’s Art Journey

In the February 1931 Asia issue, Lilian Miller stars in a photo essay, ‘Three Artists Who Transcend the Bounds of East and West.’ Displaying woodblock prints and a photo of Miller at work, the black and white spread captures her in a kimono, conveying the idealized image of ‘the artist at work’ and meek Asian womanhood.

Trained by a Japanese master, Miller’s patient copying of nature in the traditional style implies a dedication to essential Japaneseness. Woodblock prints, considered Japan’s typical art, aligned with American democratic values, appealing to common people.

In a 1932 Vassar article, Miller shared her career, influenced by her Japan upbringing. Born there, transitioning to woodblock painting felt natural. Negotiating her path reflected the challenges and freedom of the Modern Woman, interpreting between Japan and America.

Miller’s Japan outlet was creating greeting cards for expatriates, blending cultural hybridity and Orientalist appropriation. “Rain Blossoms, Japan, 1928,” showcased her talent, with faceless figures and vibrant umbrellas blending traditional motifs with technological hints.

She often presented Asia through traditional ukiyo themes, favoring landscapes over modern scenes. “Moonlight on Fujiyama, 1928,” exemplified her style, paying homage to Mt. Fuji amid contemporary artistic trends.

Timing aligned with Ansel Adams’ popularity, depicting America’s parks. Lilian Miller’s art journey embodies transcending boundaries, a pioneer bridging cultural gaps from west to east.

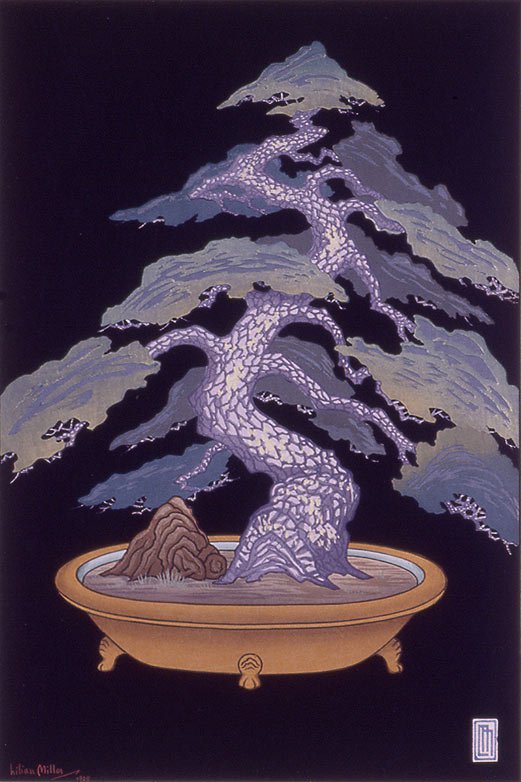

The “Dwarf Pine Tree” or bonsai is intriguing. The play of light and shadow on the bark implies a natural setting, resembling a forest. However, being in a pot indicates domestication. With no background, it exists without a clear context—whether in a forest, a house, or anywhere.

This portrayal, as an Oriental motif, suggests Asia as a picturesque landscape open to the projection of viewers’ fantasies, ready to be transplanted anywhere.

Female Independence: Lilian Miller’s Complex Identity

Kendall Brown explores Lilian Miller’s personal life, revealing a 1920 letter discussing her challenges with falling in love with a man. Brown suggests lesbianism may have influenced her decision to live in the Far East, where deviating from norms was common for Westerners.

Miller’s public persona, marked by a short haircut and the nickname ‘Jack,’ hints at potential sexual preferences. However, these attributes could also be products of the 1920s fashion and childhood nicknames, complicating any direct conclusions.

In the post-World War I era, clothing meanings were fluid, especially regarding gender identity. Laura Doan cautions against imposing contemporary assumptions about clothing and same-sex desire, emphasizing nuanced understanding of female masculinities.

Like notable women before her, Miller transgressively appropriated male costumes, wearing them privately while embracing emphatically female costumes, such as kimonos, in public.

Her art, focusing on traditional subjects, challenges Asian ‘tradition’ and Western norms. While Brown speculates about Miller’s lesbianism, limited personal papers hinder conclusive evidence.

Struggling with identity contradictions, Miller felt like a stranger in America and a perpetual foreigner in Japan, residing mostly in hotels.

Her dual identity, using ‘Jack’ with family and ‘Lilian’ publicly, reflects her complex negotiation of gender roles. In Japan, she transgressed by producing woodblock prints, traditionally male, while in the West, her carving and printing might have been perceived as appropriately feminine.

Navigating Boundaries: Lilian Miller’s Journey as a Modern Woman

Lilian Miller, a messenger between east and west, faced challenges transcending societal expectations.

Consciously performing Japaneseness and masculinity, she rebelled in Japan and traded on exoticism in America.

Alys Eve Weinbaum equates racial superiority with control over a Japanese mask, revealing one’s white modernity. Miller presented the ‘Oriental’ without the mask, performing whiteness amid exotic settings.

Her cultural cross-dressing, both in public and private life, exemplifies the performative aspects of the Modern Woman.

Navigating two distinct cultural traditions, Miller’s career symbolizes modernity in Japan and the USA.